Authoritarian kleptocrats are thriving on the West’s failures. Can they be stopped?

A hidden web of power revealed itself to Internet users in early 2022. Following a brutal government crackdown in Kazakhstan in January, anyone using open-source flight-tracking websites could watch kleptocratic elites flee the country on private jets.

A little more than a month later, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine brought a new spectacle: social media users were able to track various oligarchs’ superyachts as they jumped from port to port to evade Western sanctions. These feeds captured a national security problem in near real time: In Eurasia and beyond, kleptocratic elites with deep ties to the West were able to move themselves and their assets freely despite a host of speeches by senior officials, sanctions, and structures designed to stop them.

Kleptocratic regimes—kleptocracy means “rule by thieves”—have exploited the lax and uneven regulatory environments of the global financial system to hide their ill-gotten gains and interfere in politics abroad, especially in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union. They are aided in this task by a large cast of professional enablers within these jurisdictions. The stronger these forces get, the more they erode the principles of democracy and the rule of law. Furthermore, the international sanctions regime imposed on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine has little hope of long-term success if the global financial system itself continues to weaken.

The West still has a long way to go to rein in the authoritarian kleptocrats who have thrived on the institutional dysfunction, regulatory failure, and bureaucratic weakness of the transatlantic community for far too long. We need to rethink not just how we combat kleptocracy, but also how we define it. Policy makers need to understand that authoritarian regimes that threaten transatlantic security are closely linked to illicit financial systems. As it stands, our thinking about how foreign corruption spreads is too constrained by stereotypes about kleptocratic goals and actions.

Outdated mental images of kleptocracy hobble the West’s response

Most transatlantic policy makers have in mind the first wave of kleptocracy, which primarily flourished in the late twentieth century. Its rise was intertwined with that of transatlantic offshore finance, which prompted a race to the bottom in financial regulation and a rise in baroque forms of corruption across the post-independence “Third World.”

The corrupt autocrats of the Cold War era flaunted the wealth they stole from their own people. These kleptocrats, many of whom are still spending large today, usually did not weaponize their corruption to influence the foreign policies of the United States or its allies. They were content to offshore their ill-gotten gains in US, UK, and EU jurisdictions with lax oversight over these types of transactions.

But this mental image of the kleptocrat is outdated: These kinds of kleptocratic leaders are not extinct, but they are curtailed. It is no longer a simple matter for first-wave kleptocrats to access the global financial system. Many of the regulatory loopholes exploited by these classic kleptocrats have either already been addressed or are in the process of being closed.

The second wave of kleptocracy, which emerged since the 2000s, is more sophisticated, authoritarian, and integrated into the global financial system than its predecessor. Second-wave kleptocrats intend to use the global financial system for strategic gains—either for self-gain and/or to reshape it in their image—instead of just hiding or securing the money they have stolen. Most notably, this evolution accelerated in Russia under President Vladimir Putin before February 2022, with the agendas of oligarchs and kleptocrats being subordinated to and intertwined with the plans of an ambitious state authoritarian.

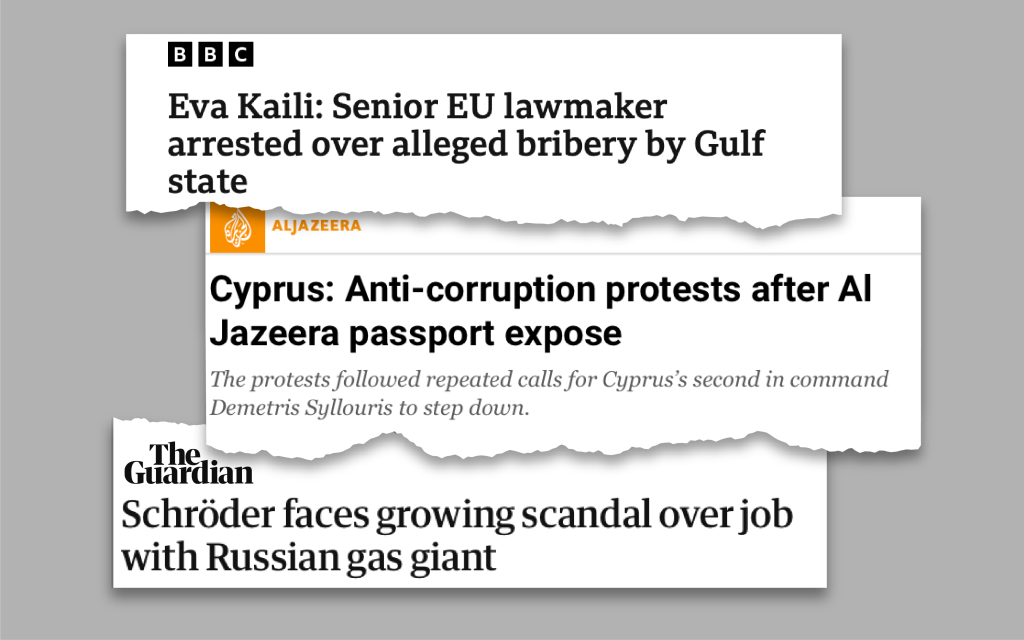

Alongside this weaponized corruption, there has arisen in the West a coterie of enablers among the policy makers targeted by second-wave kleptocrats.

The second wave of kleptocracy is more sophisticated, more authoritarian—and more dangerous

Though our understanding of the threat posed by illicit finance has grown ever more sophisticated, our conception of a kleptocrat remains frozen in the mid-to-late 2000s: halfway between David Cronenberg’s 2007 London Russian gangster movie Eastern Promises, which depicted ties between the Russian state and overseas mafia groups, and the 2011 case of Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, vice president of Equatorial Guinea, in which the US Justice Department seized a Gulfstream jet, yachts, cars, and Michael Jackson memorabilia. Both depictions—one fictional, one real—describe the world of ten years ago, when the second wave of kleptocracy was still relatively new.

So what does kleptocracy look like today?

These cases of second-wave kleptocracy show why, despite a decade of transatlantic anti-corruption activism and the sanctions imposed on the Kremlin’s cronies and war chest, the kleptocrats are still winning even as their objectives have evolved.

Chronically underregulated industries fuel the problem

As regulations have caught up to the first wave of kleptocracy, foreign kleptocrats are increasingly switching to different channels for illicit finance.

Changes in US regulations since 2001

USA PATRIOT Act passes into law and becomes effective. Title III greatly enhances AML regulations.

The Magnitsky Act is signed into law developing a sanctions mechanism against corruption and kleptocracy in Russia.

FinCEN implements GTOs for the first time.

The Global Magnitsky Act is signed into law, extending Magnitsky jurisdiction beyond Russia.

The Global Magnitsky Act goes into effect.

The 2020 AML Act passes, greatly extending AML regulations across multiple industries, and encompasses the Corporate Transparency Act.

The Biden Administration releases its national anticorruption strategy, outlining new defenses it aims to develop against weaponized corruption.

The US Depts of Justice and Treasury form the KleptoCapture unit as part of the G7 and Australia’s REPO task force to enact sanctions against the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Changes in UK regulations since 2001

The European Parliament ratifies 2AMLD. Despite coinciding with the USA PATRIOT Act, it aims to strengthen the existing provisions of the 1991 1AMLD.

The European Parliament ratifies 3AMLD. The extension of AML regulations to money services businesses and other industries is part of reforms to the UK and EU’s AML regulatory landscape recommended by FATF.

The UK National Crime Agency (NCA) is formed. Economic Crime Command is the NCA branch that deals with financial crime.

The European Parliament ratifies 4AMLD. It introduces new reporting and CDD requirements.

Criminal Finances Act is passed in the UK parliament. It introduces UWOs as a new tool for law enforcement against foreign kleptocrats.

The European Parliament ratifies 5AMLD. Despite its eventual departure from the EU, Britain adopts matching legislation.

The Money Laundering (Amendment) is passed in the UK parliament. It extends greater CDD requirements into more industries, such as for crypto exchanges and arts trades.

The Economic Crime Bill passes in the UK parliament and a new kleptocracy cell is established in the NCA. These reforms are meant to assist with global sanctions against the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Changes in EU regulations since 2001

The European Parliament ratifies 2AMLD. Despite coinciding with the USA PATRIOT Act, it aims to strengthen the existing provisions of the 1991 1AMLD.

The European Parliament ratifies 3AMLD. The extension of AML regulations to money services businesses and other industries is part of reforms to the UK and EU’s AML regulatory landscape recommended by FATF.

EUROPOL is reformed into an EU agency, extending some of its authority in investigating money laundering operations across the EU.

The European Parliament ratifies 4AMLD. It introduces new reporting and CDD requirements.

The European Parliament ratifies 5AMLD. Despite its eventual departure from the EU, Britain adopts matching legislation.

The European Union establishes the EU “freeze and seize” task force. The task force works with the G7 and Australia REPO task force to enact sanctions against the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The European Parliament ratifies the European Magnitsky Act, granting the European Commission the power to place sanctions on human rights abusers and kleptocrats.

Central to both the failure of transatlantic regulation and the strategies of second-wave kleptocrats are chronically underregulated financial industries: private investment firms, art dealerships, real estate agents, and luxury goods providers. The global arts trade industry was estimated to be worth $65 billion in 2021, with the United States, the UK, and the EU accounting for at least 70 percent ($45.5 billion) of worldwide sales.

As of 2020, the total value of assets under management in the global private investment industry was estimated at $115 trillion, more than $89 trillion of which was in the US, UK, and EU.

In 2020, the global value of residential real estate was an estimated $258.5 trillion, with North America and Europe together composing at least 43 percent of that value (approximately $111.155 trillion).

The cryptocurrency market is the newest. It is also less stable than other financial industries, so its relative size and value fluctuates more dramatically.

Weaponized corruption in action

The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal was the largest political scandal in Malaysian history and the most publicly known case of kleptocracy in the world before the release of the Panama Papers in 2016.

From 2009 to 2015 as much as $4.5 billion was stolen from Malaysia’s state-owned investment fund—designed to boost the country’s economic growth—into a variety of offshore accounts and shell companies.

The stolen funds were channeled through multiple jurisdictions, including in the British Virgin Islands and the Dutch Caribbean country of Curaçao, before being passed through US-based private investment firms.

The US Department of Justice believes the funds were “allegedly misappropriated by high-level officials of 1MDB and their associates, and Low Taek Jho (aka Jho Low).”

Instead of being used for economic development in Malaysia, the funds were used to buy real estate in California, New York, and London; paintings by Monet and Van Gogh; and stakes in luxury hotel projects in New York and California, as well as laundered into the film industry as funding for the 2013 film The Wolf of Wall Street.

The film’s production further resulted in the exchange of fine art purchased with dark money, such as pieces of art by Pablo Picasso and Jean-Michel Basquiat that were gifted to actor Leonardo DiCaprio because of his starring role in the film. (DiCaprio returned the paintings to US authorities upon learning how they were acquired.)

The scandal implicated Malaysia’s then-prime minister Najib Razak, alleged to have channeled approximately $700 million into his own personal bank accounts, along with several people close to him.

Photos: Reuters

A large amount of the stolen wealth remains in US real estate and fine art, which the Department of Justice is continuing to recover on behalf of Malaysia. As of August 2021, more than $1.2 billion had been recovered. Yet, given the number of private investment firms, real estate traders, film producers, and arts dealers that were involved in the 1MDB-related illicit finance, it is highly likely the stolen funds have been dispersed across a variety of industries. With better financial intelligence sharing between US, UK, and Dutch authorities, these suspicious dark money flows might have been identified before the money was moved across US financial institutions.

What needs to happen to take on the second-wave kleptocrats?

The US, UK, and EU need a more structured relationship to develop anti-corruption policies. We propose a new mechanism for the transatlantic community to harmonize its necessary response: a Transatlantic Anti-Corruption Council to coordinate anti-corruption policies between the United States, the UK, and the EU. It could connect the various US, UK, and EU agencies and directorates that work on corruption and kleptocracy-related issues, and organize them into expert groups focused on illicit finance, tax evasion, acquisition of luxury goods, and more. Recent cases of weaponized corruption have exploited the lack of regulatory coordination and financial intelligence sharing between transatlantic jurisdictions to evade detection and to corrupt transatlantic democratic and financial institutions. The TACC can work on closing these gaps—but it is only the beginning of a larger transatlantic strategy against weaponized corruption.

The anti-corruption policy to-do list

United States

In the United States, much of the problem stems from a lack of legislation enabling more comprehensive law enforcement and regulatory compliance within these underregulated industries. The United States should:

- Follow through on the US legislative national anti-corruption strategy. Many of the existing flaws in the US regulatory sphere were correctly identified and should be addressed accordingly. This includes the strategy’s commitment to increasing regulation on the private investment industry, including on firms managing assets totaling less than $100 million.

- FinCEN, the US FIU, is chronically understaffed, underbudgeted, and relies on outdated technology. Even if legislative reform was passed and/or executive action taken to extend BSA/AML obligations to more financial institutions, FinCEN would be hard-pressed to fully investigate reports it received and to enforce its authority in cases in which financial crime was present.

United Kingdom

The UK, on the other hand, already has much of the legislation it needs to address anti-money-laundering (AML) deficiencies and sanctions evasion occurring in its jurisdictions. It needs to implement that legislation—and address the close connections between the City of London and British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. The UK should:

- Share legalistic principles and good practices of unexplained wealth orders (UWOs) with allies. UWOs have already proven to be very effective in bringing more investigative power to bear on to foreign kleptocrats based in the United Kingdom

- Reduce regulatory mismatches between the primary UK jurisdictions and the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories, especially with beneficial ownership registries and sanctions compliance

- Improve verification standards for companies registered in Companies House to identify shell companies

- Fully implement and enforce existing transparency and national security laws, especially the National Security and Investment Act

European Union

Much like the UK, many of the EU’s problems stem less from a lack of legislation than from the implementation of those policies. The EU faces additional hurdles in ensuring that all its member states harmonize their AML policies. The EU should:

- Increase compliance requirements for private investment firms managing assets totaling less than €100 million

- Fully implement the 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD) across EU jurisdictions. The establishment of an EU Anti-Money Laundering Authority will be essential for harmonizing regulations across the European Union (EU).

- 6AMLD measures should also be applied to overseas autonomous territories like Aruba.

- Increase enforcement of laws that prohibit the spread of corruption in foreign territories, particularly for cases that involve spreading corruption to fellow EU member states

Transatlantic community

The transatlantic community should:

- Work closely with the United States in its national anti-corruption strategy. The strategy’s success will be heavily dependent on the degree of cooperation between US allies and the Biden administration in its implementation.

- Match regulatory legislation on both sides of the Atlantic. This will permit better coordination of sanctions between allies and reduce tensions between the United States and its allies when the United States relies on extraterritorial action.

- Create channels for financial intelligence units and private sector actors in transatlantic jurisdictions to share information about suspicious clients, transactions, and transfers. The Europol Financial Intelligence Public Private Partnership (EFIPPP) may be a good platform for increased intelligence sharing.

- Establish the Transatlantic Anti-Corruption Council (TACC). Its main purpose would be to coordinate legislation on improving anti-money laundering/Know Your Customer (AML/KYC) policies, share good governance policies (such as beneficial ownership registries) to harmonize regulations, crack down on sanctions evasion, and share financial intelligence on transnational financial criminals to shut down their operations.

- The TACC should also regularly convene expert working groups on, at a minimum:

- trade-based illicit finance,

- market-based illicit finance,

- bribery and other enabling forms of corruption,

- acquisition of luxury goods by kleptocrats,

- asset returns,

- tax evasion,

- terrorist financing, and

- future threats.

- Financial intelligence working groups should similarly cover individual cases of financial crime at the tactical level. At the executive level, primary stakeholders in the TACC should be

- the Departments of State, Treasury, and Justice, and USAID on the US side,

- the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO); His Majesty’s Treasury; and the Home Office on the UK side, and

- the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs; Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union; and Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers on the EU side

The late United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan once said: “If corruption is a disease, transparency is a central part of its treatment.” Annan spoke in a time before the crisis of weaponized corruption rose to prominence, but his words ring clearer now that foreign kleptocrats are spreading their malign influence by means of the money they stole from their own people. The United States and its allies must choose the partners with which it engages more carefully. Otherwise, it may find that some of its partners are in fact proxies for strategic competitors of the transatlantic community who will undermine the West’s security and the integrity of its democracies from the inside.

Related content

Image: A protester holds a 'Seize Londongrad Assets' placard during the demonstration. Thousands of people gathered in Whitehall in protest against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and called on the UK Government and NATO to help Ukraine. (Photo by Vuk Valcic / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)No Use Germany.