How the IMF can navigate great power rivalry

Introduction

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was launched in 1944, charged by its forty-four founding members with “monitoring the international monetary system (IMS) and global economic developments to identify risks and recommend policies for growth and financial stability,” among other things. As key features of the world economy and its monetary system have changed over time, the IMF has responded and adjusted its functions as well as its analytical and policy framework to remain relevant and useful to its membership, now 190 countries.

There have been several fundamental changes in the IMS, posing different challenges for the IMF. In the first three decades of its existence, the IMF served as an overseer of an international fixed exchange-rate regime—with most other currencies pegged to the US dollar (USD), which in turn was linked to gold (at $35/ounce). The IMF mission was to ensure that exchange rates were fixed at appropriate levels and to identify the need to adjust currency parities from time to time to rectify underlying imbalances—basically to countenance such adjustments and not allow them to be used to gain unfair competitive advantages. After the United States suspended the convertibility of the USD to gold in 1971 and the oil shock of the mid-1970s, the IMF supported a freely floating exchange-rate system, arguing that this would enable countries to absorb shocks to their trade balances and economies caused by external factors—and in the process, expanding the range of policy issues it deals with. In particular, the IMF encouraged a free movement of capital to help developing countries augment their insufficient domestic savings with imported capital to grow their economies. In this context, the IMF advocated liberalization, deregulation, and other structural reforms to reduce rigidities in the economy, enabling markets to function more efficiently, thus attracting capital inflows. As capital flows have increased, debt has accumulated, leading to a series of sovereign debt crises beginning in the 1980s. The IMF has had to require debt restructuring as a condition for restoring financial sustainability before an IMF program can be approved. This task has become more difficult as the composition of creditors to developing countries has become complex and numerous. With the start of the new millennium, climate change has been recognized as posing increasingly tangible threats to financial and economic sustainability, prompting the IMF to adjust its mission to help mitigate climate change risks and support the green transition and sustainable development.

More recently, geopolitical competition and conflict between China and the United States, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have fragmented the world on political, economic, trade, and financial fronts. These fragmentations, including of the monetary and financial system, have posed a serious challenge to the fulfillment of IMF core missions in three important dimensions. First, heightened mistrust and even hostility between key countries have undermined their willingness and ability to cooperate to forge common responses to global challenges. This has interfered with the functioning of many international organizations, transforming fora for cooperation into venues of competition. This could eventually threaten the still-normal operation of the IMF—as well as the World Bank.

Second and more concretely, the policies adopted by key countries to promote a broad concept of national security that includes economic security and environmental and social protection—in particular trade/investment controls and industrial policy—have significantly deviated from the IMF’s theoretical model of essentially open market economies and free trade. Such a model has served as a normative template for IMF assessment and recommendations to all members as well as policy conditionality for its assistance programs for members in need. The IMF now faces the challenge of reconciling its free market model with the new concerns of its important members—either by persuading them to refrain from or minimize deviations from its traditional model, or internalizing those concerns in its model and, in the process, changing the orientation of its policy advice.

Finally, given the geopolitically driven fragmentation of the world economy, the IMF has to discharge its core mission of finding ways to promote economic growth and financial stability—now being constrained by loss of economic efficiency.

The rest of the report will analyze each of these three dimensions in details, sketch out the challenges they pose to the IMF, and suggest some ways to deal with them.

I. Great power competition raises mistrust and undermines cooperation

The US-China strategic competition has been in the making for the past decade but accelerated in 2017 when newly elected President Donald Trump criticized China’s unfair trade practices as causing substantial and persistent US trade deficits and hollowing out its manufacturing base. The criticism was followed by the United States unilaterally imposing tariffs on imports from China in an attempt to rectify the trade imbalances. A dispute ensued that has quickly deepened and widened to other fronts of the US-China relationship and relations with their respective allies.

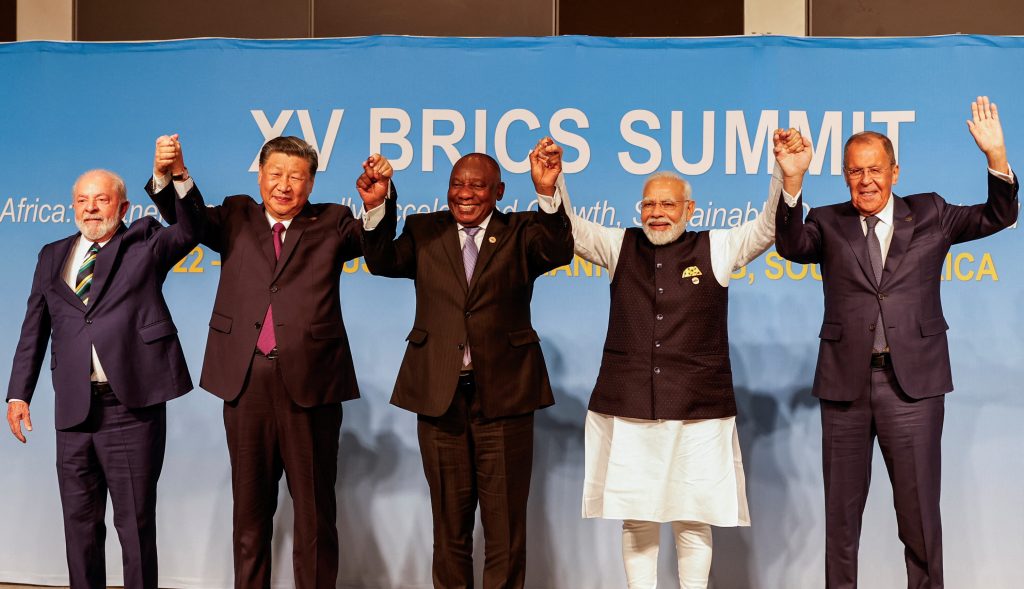

Essentially, the strategic competition is rooted in resentment as China—a growing economic and political power—continues to grapple with the post-World War II global order and institutions essentially established by Washington and its Western allies, and seeks to overturn that world order in favor of a new one aligning with its vision and interests. This overriding goal has been articulated by successive generations of Chinese leaders, most recently by Xi Jinping in October 2022 as “fostering a new type of international relations.” More importantly, many other countries share the desire to replace the US-led order with a multipolar system, in which large emerging market (EM) countries have more of a voice in shaping the rules and decisions in international affairs. Specifically, it has been proclaimed as the common goal of the China-Russia “partnership without limits,” the BRICS grouping (Argentina, Brazil, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and the United Arab Emriates), and other major EM organizations and fora.

Understandably, the United States has declared that it is in its national security interests to defend and preserve the post-WWII order that has helped to engender peace and prosperity in most of the world for many decades, and to push back against China’s efforts to weaken and change that order. This objective has been articulated in US and (more recently) German national security strategies. It also was reflected in the messaging from the latest Group of Seven (G7) summit meeting in Japan—pointing at China as the rival power pushing for change in the status quo.

The two camps’ competition for influence in shaping the global order has impacted the functioning of existing international institutions set up after WWII to facilitate international interactions. Instead of being fora for cooperation as originally intended, these institutions—including the United Nations and its affiliated organizations like the Human Rights Council and Commission, the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), etc.—have become venues for competition. So far at the expense of the United States and Europe—specifically by pulling together a majority of member countries that vote in support of China’s positions. This has been clear in cases of defending China against Western charges of: human rights violations against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, lack of transparency and cooperation in investigating the origins of COVID-19, and blocking Taiwan from participating in some of these agencies’ work (i.e., the WHO or ICAO).

At the same time, China has launched alternative institutions to provide venues for cooperation among like-minded countries while excluding the United States. In addition to participating and hosting a series of government-to-government groups like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China has regular summit meetings between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Central Asia, Africa, Middle East, and Latin America groupings. In addition, China created international development banks such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and, as a BRICS member, is a founding member of the New Development Bank (NDB). The aim is to build up alternative international institutions to facilitate cooperation between China and other countries on China’s terms and not under the tutelage of the United States and Europe—which has contributed to the fragmentation and weakening of the current global order and its institutions.

Specifically, the strategic competition has weakened the UN and many of its affiliated agencies as well as the World Trade Organization (WTO), but so far has not impacted much the functioning of the IMF (or the World Bank). During the coronavirus-related global economic shock, the IMF has made available $250 billion, or 25 percent, of its lending capacity to member countries; initiated and mobilized support for a special drawing right (SDR) to allocate an equivalent of $650 billion to all members. These IMF actions helped many members in need of liquidity support and assisted the G20 to launch the Debt Service Suspension Initiative and then the Common Framework for Debt Treatment to assist low-income countries (LICs) in or near sovereign debt crises. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the IMF was quick to give Ukraine two emergency loans valued at $1.4 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively; and last April, the IMF approved a $15.6 billion four-year program catalyzing $115 billion of financial support for Ukraine from Western donor countries. The IMF also launched a Food Shock Window to help poor members suffering from the war-related shortage and high prices of grains, and a Resilience and Sustainability Trust to provide long-term, affordable financing to low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries to deal with the impact of climate change and invest in a green transition.

Despite those worthy achievements, it is nevertheless reasonable to suggest that without the strategic competition and heightened mistrust among major countries in the background, more could have been done to help LICs and other vulnerable countries during the crises caused by the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—amid struggles in dealing with climate change and reducing poverty. It is sobering to look at the gap between what has been done and what is needed for LICs to achieve sustainable development—estimated to be $2.5 trillion per year. With stronger international cooperation and support, the IMF and World Bank could have provided more financial assistance, including risk-sharing facilities to help catalyze private investment as well as facilitating more debt relief to LICs. It also is important to note that the IMF’s ability to continue functioning and responding to crises may owe a lot to its current governance structure: voting power is weighted by members’ capital contributions, as reflected in their quotas and voting shares. Accordingly, the United States commands 16.5 percent of the total votes,1The United States has a 17.43 percent quota share, but since members have 750 basic votes plus one vote for each SDR 100,000 of quota, its voting share is slightly lower—but still allows it to veto major decisions requiring a super majority of 85 percent of the votes.

and the G7 has 41.25 percent of the voting shares—comfortably putting the West in general in the driver’s seat for most IMF activities and projects: a simple majority is required, but approval by consensus is typical. In other words, the IMF is still essentially a Western-driven institution, which can explain why it has functioned relatively smoothly, including approving potentially controversial programs such as that for Ukraine; the IMF usually carries out programs with countries after a conflict, rather than during a war.

However, it remains an open question how well the IMF can carry out its missions and how long its current governance structure can last if the existing geopolitical conflicts continue to escalate. Going forward, the deepening of the strategic contention could begin to hamper the functioning of the IMF. Fundamentally, the rising level of mistrust and at times hostility between the United States and China would make it very difficult to develop international consensus to reform the governance structure of the IMF to give more voice and representation to emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs)—so as to be more commensurate with their growing weight in the global economy.

An ongoing reform effort has been negotiated as part of the IMF’s sixteenth quota review, scheduled to be concluded by December 15, 2023. The quota review includes the task of revising the quota formula to support an increase of quotas to augment the permanent financial resources of the IMF. Currently, permanent resources account for less than half of the IMF total lending capacity of SDR 713 billion ($950 billion), with the remainder funded by the New Arrangement to Borrow of SDR 361 billion, which is scheduled to expire in December 2025, and the bilateral Borrowing Agreements for SDR 139 billion, expiring at the end of this year but extendable to year-end 2024 if creditor countries agree to do so. In the past, the borrowing arrangements were extended routinely without much fanfare; in the current global tension, that should not be taken for granted. While the probability of not extending the borrowing arrangements is low, the failure to do so would have a significant impact in sharply curtailing the IMF’s lending capacity and its ability to help countries in need.

More importantly, the quota review will try to reach agreement to distribute quotas in a way that would raise the voting power of the EMDCs. In the current environment of tension and mistrust, it is highly unlikely that a redistribution of voting power in favor of EMDCs—especially China—will be supported by the United States and other Western countries. Consequently, the sixteenth IMF quota review is destined to expire without producing any results. As such, the underlying unequal voting power will continue to fester as a source of discontent in the Global South, posing a threat to the legitimacy of the IMF.

In addition, weakened cooperation has made it more difficult to come up with new and necessary initiatives requiring strong international consensus. For example, it would be difficult to get support for another round of SDR allocation, as has been suggested by countries and civil society organizations. The IMF has recognized the difficulty in building international consensus in multilateral efforts, suggesting that a plurilateral approach involving smaller groups of like-minded countries can be a practical way forward. However, there are limitations to the plurilateral approach, as evident in the recent Paris Summit for a New Global Financing Pact.

More pressing for developing and low-income countries (DLICs) has been the lack of progress in the IMF’s (and World Bank’s) efforts to promote the Common Framework for Debt Treatment to deal with the growing sovereign debt crisis of DLICs. In their latest initiative, the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, these institutions have promised information sharing to all creditors including private ones and concessional loans or grants to the LICs in debt crises—hoping to speed up several debt restructuring operations under the Common Framework. Since its launch in 2020 by the G20, only four countries (Zambia, Chad, Ethiopia, and Ghana) have applied to restructure their sovereign debt under this framework, and most have languished in the process without much progress (except for Zambia, which just got its debt restructuring deal). Meanwhile, DLICs have incurred more than $9 trillion of debt, of which a $3.6 trillion portion represents long-term public external debt with 61 percent owed to private creditors. In particular, seventy-five LICs eligible for International Development Association concessional loans are being burdened with almost $1 trillion in debt; with more than half of them already in, or at high risk of being in, debt distress.

One particular policy tool, Lending into Official Arrears (LIOA), has been developed to deal with situations where a debtor country has accepted the conditionality for an IMF program, but cannot get all of its official bilateral creditors to agree to a restructuring deal to help the country meet the Fund’s financial sustainability requirement. In that case, the IMF can lend to the country in question while allowing it to stop servicing its debt to the bilateral creditor which has refused to participate in a restructuring deal. This situation applies to China in several LIC cases, such as Zambia, where the country had reached IMF staff agreement for a program at the end of 2021, but progress toward board approval was held up until late August 2022 and disbursement delayed until late June 2023—by a failure of bilateral creditors to reach a debt restructuring deal. Western countries attributed this failure to China’s reluctance to accept a reduction in the principal amount of debt and its preference to conclude a bilateral deal with debtor countries. Eventually, a restructuring deal for Zambia’s $6.3 billion debt to bilateral creditors was reached consistent with China’s preferences—extending maturities of the debt to 2043 at lower interest rates, with no cut in face value to reduce the present value of the debt by 40 percent. This deal is useful but insufficient to meaningfully reduce Zambia’s debt load, which is estimated to exceed $18 billion. In any event, the IMF has not been able to use the LIOA tool to deliver needed support to Zambia—probably fearing opposition from China as well as facing reluctance by the debtor country to be unfriendly to China.

In short, escalating geopolitical conflicts would make it more difficult for the IMF and World Bank to continue functioning normally in the future.

II. Policies to promote derisking have deviated from the IMF template

The strategic competition so far has taken place mainly in the economic, financial, and high-tech areas—driven by efforts from both sides to reduce the risk of exposure and vulnerability to each other. As reflected in the latest G7 summit communique, the West appears to coalesce around the concept of derisking (rather than decoupling) vis-à-vis China— realizing that it is impractical and quite costly to economically decouple completely from China. The concept of derisking—coming after a string of notions such as reshoring, near-shoring and friend-shoring—is vaguely defined to encompass controlling trade and investment transactions with China concerning high-tech products and know-how in advanced semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing and other areas, especially those with military applications. It also includes reducing reliance on China for strategic industrial inputs such as critical minerals like rare earths, which are essential for high-capacity batteries and the world’s effort to transition to green energy.

The motivation behind derisking, however, seems to differ between the United States (wanting to preserve or even widen its lead over China in high-tech and related military capacities) and the European Union (aiming to reduce its dependency on China in a few specific areas). The US approach is more offensive in nature and has been perceived by China as hostile efforts to contain its rise—deepening mistrust and prompting retaliation. The difference in motives has also tempted China to try to prevent Europe from being fully aligned with the United States, giving Beijing more room for maneuver.

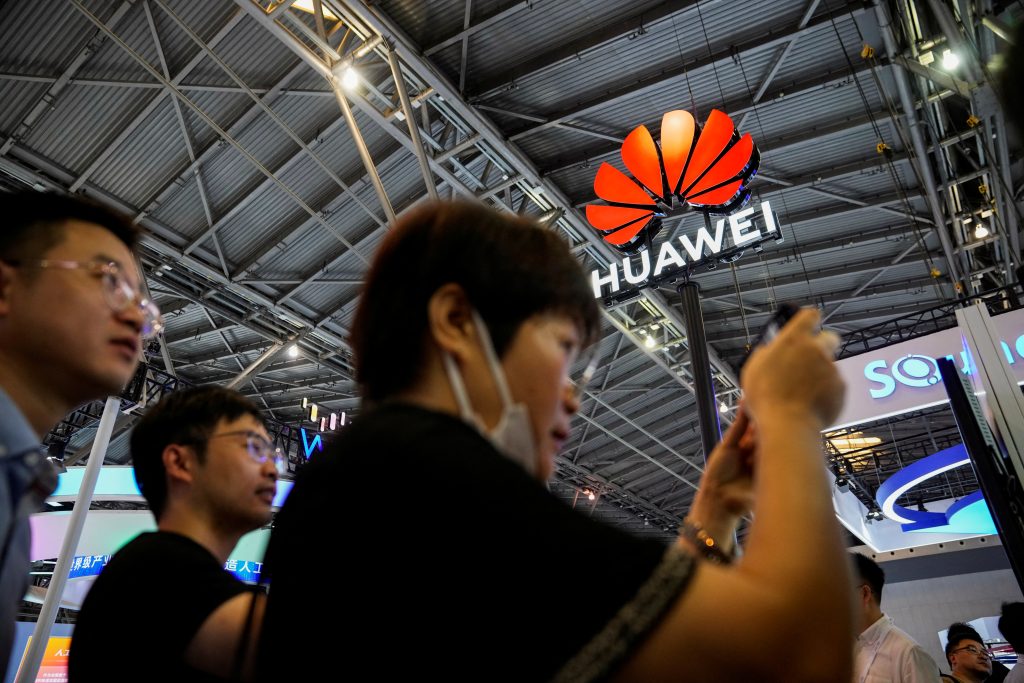

Western derisking efforts have been implemented via trade and investment controls and industrial policy to promote national champions in high-tech and other critical areas. The United States—under both President Trump and President Biden—has increasingly controlled the export of advanced chips, along with the hardware and software needed to produce them, to an increasing number of Chinese entities. It’s likely that the range of high-tech items under export control will be expanded in the future, with an aim to delay Chinese progress in critical and dual-use technologies such as AI, quantum computing, and biotech, among many others. The United States has also strengthened its Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and significantly increased its screening to restrict Chinese investment in a broad range of US companies. The Biden administration and Congress are finalizing rules to impose outward screening of investment to China, in particular in advanced semiconductors, quantum computing, and AI. Specifically, the US government has invoked national security to ban Huawei’s equipment from being used in the US telecom infrastructure and is in the process of banning ByteDance’s TikTok.

The United States also has embraced industrial policy by passing a series of laws including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (aka Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), the CHIP and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act—all designed to incentivize high-tech investment and manufacturing in the United States through the use of subsidies, tax incentives, and other favorable regulatory treatments. This, however, has unleashed a subsidies race between the United States and EU countries.

Many US allies in Europe and Japan have adopted similar but milder measures including the screening of inward foreign investment and possible outward investment, and restricting sales of advanced chips and chip-making technologies to China while promoting chip production in the EU (via the European Chips Act). The EU also has launched the Critical Raw Materials Act to reduce its dependencies on countries that are not union members. Some European countries have restricted the use of Huawei equipment in their telecom infrastructures. More generally, trade protectionist measures have been on the rise: as of 2020, the G20 countries—instead of setting examples in trade liberalization—had adopted them.

At the same time, China and its allies have also tried to derisk by reducing their vulnerability to the G7 use of economic and financial sanctions—especially after the unprecedented sanctions on Russia after its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Of particular concern: the G7’s decision to freeze the foreign reserve assets that the Bank of Russia held in the G7 economies. China and its allies’ derisking mainly involves increasing bilateral trade and investment activities, and developing alternative—essentially bilateral—means of settlement for cross-border transactions to avoid use of the US dollar.

The measures highlighted above, done in the name of protecting national security on both sides, have significantly deviated from the IMF model and norms of an open, rules-based market economy with free trade, and where the role of government is limited to ensuring a free, well-regulated, and competitive marketplace where private firms and consumers determine the supply and demand of goods and services, resulting in an optimal allocation of resources in the economy, both domestically and globally. The essentially open and free market model has been used by the IMF as the normative template to assess the economic performance of member countries and give them advice in its regular Article IV consultations. More importantly the model underpins the conditionality required for IMF assistance programs to countries in crises.

In addition to the national security concerns and subsequent protectionism measures highlighted above, the EU has increasingly used regulatory and tax measures to promote compliance with its strict environmental protection standards (such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism), while the US government has strengthened its trade regulations to promote labor standards (such as the wage requirements for auto workers in Mexico in the United States-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement).

To be fair, this “orthodox” model has been tweaked at the margin by the IMF’s evolving policy of maintaining a decent level of social safety net (also to help build public support for IMF programs), and acquiescing to countries imposing temporary capital controls to dampen disorderly capital flows. However, these measures basically involve setting priorities in fiscal policy and using temporary capital control measures, and not fundamentally moving away from the IMF’s model.

As a consequence, the IMF has to find ways to reconcile its free market model with the reality of trade/investment controls and industrial policy practiced by an increasing number of important member countries—contradicting key IMF advice and lending conditions pushing for deregulation and liberalization of economic and trade activities. In fact, the IMF needs to rethink its model anyway as more and more members of the economic profession have conducted new research using rigorous empirical methods, finding that industrial policy has been more ubiquitous than thought and can bring economic benefits if implemented properly. As a consequence, the IMF has to either specify well-defined exceptions to its model, where such control measures can be used with minimum distorting and disruptive effects, or modify its model to internalize national security and environmental and social concerns, with more accurate measurements of the costs and benefits of such interventions in the market. Doing so would change the orientation of its policy advice.

Practically, the IMF needs to develop a new economic model, in which the objective function contains multiple goals, not only maximizing output and employment at stable prices, but also securing national security, achieving net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, and reducing economic and social inequality. Some of these objectives are at odds with each other, making the assessment of tradeoffs very important. The constraints also have increased to reflect all the negative consequences of fragmentation, beyond the traditional financial and technological limits.

Given the difficult challenges of coming up with such a new model, the IMF, at the very least, has to analyze and estimate/quantify the potential benefits of enhanced national security and environmental and social protection, compared with the costs in terms of losses in economic efficiency resulting from those measures. This analytical work can provide some help to member countries in navigating the geopolitically fragmented world—especially in finding ways to limit the downside impacts of derisking policies.

III. Coping with the consequences of fragmentation

The fragmentation of global trade, payment, monetary, and financial systems as well as declining international cooperation for scientific and technological research and development has already had a negative impact on the global economy. The negative effects will accumulate and become more tangible over time. The IMF will need to find ways to help members mitigate against such poor development prospects.

The breakdown of the open rule-based trading system

The geopolitical contention between key countries has weakened the open rules-based trading system anchored by the WTO. Basically, the WTO has not been able to facilitate any multilateral rounds of trade liberalization since its inception in 1995. Instead it has had to settle for several plurilateral agreements among smaller sets of willing countries for specific trade issues. These may be second-best solutions in the absence of multilateral agreements, but they have splintered the global trading system into a growing number of regional and plurilateral trade agreements. As of now, there are more than 350 regional trade agreements (RTAs) between various countries around the world, making it more complex and costly to trade across borders, especially for EMDCs.

Importantly, the US refusal to agree to the appointment of members of the Appellate Body has rendered the appeal process in the important WTO trade dispute-resolution mechanism inoperable—undermining a key function of the WTO.

Partly reflecting geopolitical tension, the annual growth rate of world trade has slowed to 1.9 percent this year, relative to global economic growth of 2 percent; the volume of trade in goods has fallen while that of services (accounting for 22 percent of total trade) has risen. Going forward, world trade is estimated to grow by 2.3 percent per year through 2031, while the global economy is expected to grow by 2.5 percent—a reversal of the traditionally faster growth of world trade stimulating economic growth in most of the postwar decades. The geopolitical pattern of trade has also changed, with China’s exports having clearly shifted from the West to the Global South (including BRICS countries)—reaching $1.6 trillion a year to the Global South, compared with $1.4 trillion to the United States, Europe, and Japan combined.

Fragmented payment system

To reduce the vulnerability to US sanctions that deny banks and financial institutions of targeted countries access to SWIFT and clearing and settlement of USD transactions through the US banking system, other countries have tried to develop ways to settle trade and investment transactions among themselves without using the dollar. So far these efforts have resulted in a network of bilateral deals, mainly between China and another country, making use of bilateral currency swap lines (CSLs) between the renminbi (RMB) and another domestic currency. Since 2009, the People’s Bank of China has arranged CSLs with about forty-one countries, for a combined valuation of $554 billion. The CSLs have been increasingly used to settle cross-border transactions as well as for China to provide emergency liquidity lending and balance of payment support to developing and low-income countries (DLICs) in crisis—estimated to have reached $240 billion, or over 20 percent of total IMF lending over the past decade. The CSLs have been complemented by the various offshore RMB deposit markets, the most important of which is Hong Kong—reported to amount to RMB 833 billion ($115 billion) at the end of April 2023. The cross-border RMB transactions have been facilitated by the maturity of China’s Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which was launched in 2015 and cleared transactions valued at $14.1 trillion in 2022 with 1,420 financial institutions in 109 countries.

Those efforts are not really aiming to replace the dollar in the global payment system, which is very difficult to do given the breadth and depth of the well-regulated US financial markets serving the largest economy in the world; they are mainly intended to reduce—or derisk— those countries’ vulnerability to US sanctions to some extent. The fact that the Russian economy has managed to function in the face of US/Western sanctions, including the exclusion of many Russian banks from the SWIFT and CHIPS systems, has motivated other countries vulnerable to Western sanctions to further develop these alternative settlement mechanisms. Those efforts to use local currencies in cross-border payments can be observed in a broad range of countries and regions; from Russia to India, ASEAN to the African Union and BRICS member countries.

As a consequence, the global payment system has been fragmented: the dollar still enjoys the key role in the system, but more and more cross-border transactions are being conducted without using it, and on a bilateral basis using local currencies. This will make global cross-border payment transactions—already cumbersome and costly—even less efficient and transparent, imposing a growing risk and cost on the global economy. This environment also will make it harder for the IMF to meet its mandate and improve the working of the global payment system, as suggested by the G20 roadmap released in 2020.

Moreover, different countries have adopted different approaches to the development of a central bank digital currency (CBDC). China is quite far ahead of other countries in terms of prototyping and testing its digital yuan, or eCNY, while the United States has shown a growing degree of skepticism toward a CBDC, which many conservative US politicians oppose. When CBDCs begin to be rolled out in other countries, that would likely add another dimension of fragmentation in the global payment landscape as the lack of communicability and interoperability among different CBDCs will create serious challenges for global payment system and financial stability.

Fragmented financial system

According to recent IMF reports, fragmentation can be observed in international financial activities. Specifically, foreign direct investment (FDI) and banking and portfolio investment flows have tended to focus on recipient countries perceived to be politically more friendly to originating countries than otherwise. As a result, the IMF has estimated a reduction of about 15 percent in bilateral banking and portfolio flows. This differentiation in investment transactions has reduced the efficiency of capital flows to EM countries, undermining growth rates in many EMDCs.

Moreover, the fact that China has made use of its extensive bilateral currency swap lines to provide emergency liquidity to friendly countries has complicated the IMF’s premier role in coordinating the timely activation of the multitiered global financial safety net.

Recent IMF research has estimated that the cumulative potential losses of output could be substantial—up to 7 percent for the global economy and up to 8 to 10 percent for some countries, given the addition of technological decoupling. Such losses would reinforce the effects of worsening demographics—the aging of society and decline in the labor force—by lowering potential growth rates in the future, which are estimated to slow to 2 percent per year in the next twenty years, compared to growth rates of 2.7 percent per year in the previous two decades. This anticipated slowdown would compound the various headwinds confronting many countries. Furthermore, financial fragmentation could increase the risks to global financial stability by triggering volatile capital flows in reaction to geopolitical tensions, while weakening the global financial safety net.

In this challenging scenario, the IMF would need to find ways to mitigate the negative impacts of financial fragmentation: advising members on how to sustain economic growth and financial stability while the global geopolitical situation continues to deteriorate, reducing potential economic growth rates and limiting available resources including FDI that governments can mobilize to address the challenges facing them. Against this backdrop, the IMF can continue to add value to members by identifying reforms and especially by providing technical assistance to implement changes in administrative processes, including the focused digitalization of government services, which could improve transparency and reduce corruption. These measures may not require significant budgetary resources and can help improve business performance, thereby supporting growth. In any event, the task of finding ways to sustain growth is intellectually challenging since simple economic efficiency is no longer necessarily the shared goal among members, as many now want to pursue multiple objectives through economic policymaking. Several of those objectives may be at cross-purposes and are likely to produce unexpected and unwanted side effects—which the IMF should monitor closely and report promptly.

Conclusion

The IMF and other international organizations are products of international cooperation. The IMF’s mandate, resources, and ability to assist members depends on the willingness and ability of key countries to work together for common solutions to shared global challenges. In that sense, the future of the IMF is not in the institution’s hands, but those of its members. Against that reality, the IMF can still find ways to leverage its practically universal membership to support necessary measures to the extent possible. It can also depend on its formidable institutional strength, especially its staff’s analytical prowess, to be helpful to members. In particular, the IMF should focus on analyzing the cost and benefits of geopolitical contention, and the resulting fragmentation of the world economy and financial system—like it began to do around the time of the spring 2023 meetings. This may not be sufficient to persuade major countries to reverse their geopolitical contention, but the IMF should be able to help those countries adopt the policies that are the least damaging to the global economy, with particular focus on limiting the negative spillovers of their policies on low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries.

Related content

About the author

Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, a former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance, and former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.