The US Space Force has started looking at setting up a civilian reserve satellite fleet. Officially titled the Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve (CASR), this collection of commercial satellites would be dedicated to assisting the military during emergencies in which the Department of Defense’s (DOD) satellite capabilities fall short. Assembling such a fleet is wise, as the Pentagon’s highly sophisticated, expensive large satellites are critical to the military’s functions; but they’re also “fat juicy targets” because of their high vulnerability to adversary anti-satellite weapons (ASATs), as General John Hyten said in 2017 when he was vice chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The Biden administration’s recent National Defense Strategy set the DOD on a mission to reduce adversaries’ disruptive ability by “fielding diverse, resilient, and redundant satellite constellations.”

The announcement of the CASR represents the logical next step for bolstering defense in space. Moving forward, a civilian reserve satellite fleet could, in alignment with the Biden administration’s “deterrence by resilience” goals, minimize the fallout from hostile action against US satellite networks and thus reduce the temptation for adversaries to mount an attack.

The US military has relied on satellites for more than thirty years. From Global Positioning System-enabled, precision-guided munitions that helped the US military destroy Iraqi tanks to spy satellites that helped track down al-Qaeda training camps, space assets were a crucial part of the first Gulf War and war on terror.

China and Russia recognize how much the US military depends on satellites. Both have developed a wide range of ASAT capabilities that can disable or destroy US space assets. These capabilities include electronic warfare, cyber operations, jamming, directed energy, and destructive kinetic ASAT weapons. China also possesses commercial and scientific satellites with maneuvering capabilities that could serve as ASATs by violently colliding with US space assets.

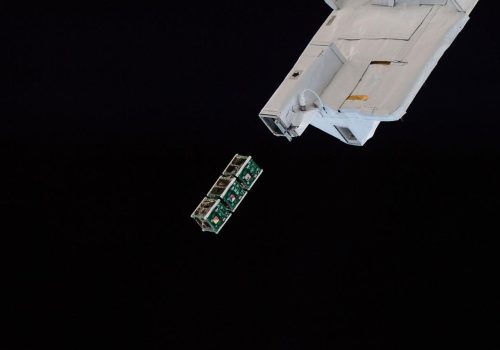

To mitigate the threat from adversary ASATs, the US Space Development Agency is bolstering space resiliency by purchasing hundreds of small (and cheap) low-Earth orbit satellites. Rather than relying on large, expensive geosynchronous-orbit satellites, this new approach will require any adversary seeking to disrupt US space capabilities to knock out not just a few exquisite satellites but a few hundred small satellites.

By announcing CASR, the United States is beginning to take steps to improve its resilience even more: Rather than relying on government-owned space assets numbering in the hundreds, the United States is hoping to enlist massive commercial satellite constellations numbering in the tens of thousands for use in emergencies.

Commercial satellites have proven their utility for security purposes during the war in Ukraine. SpaceX’s Starlink is providing the Ukrainian military with high-speed internet, allowing forces to stay in contact with each other and with Ukrainian high command. It also allows units to deploy weapons systems such as precision-guided artillery, drones, and loitering munitions. Commercial satellites have also tracked the Russian military buildup and revealed Russian atrocities in the Ukrainian cities of Izyum and Bucha. The Ukraine example shows that a civil reserve satellite fleet would thus not only increase resiliency but also expand capabilities that the US military can draw upon in times of crisis.

A civil reserve fleet is not a new concept. The US Air Force has the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, which allows the United States to expand its capacity quickly during wars or national emergencies. In twenty-first-century warfare, militaries are exceedingly reliant on a stream of satellite-provided data and services. A civil reserve satellite fleet will ensure that stream remains steady.

In setting up a civil reserve satellite fleet, the US government should do the following:

- Create a preferential contract award system for private-sector participants in the program.

- Create fixed payment structures for the services private-sector participants provide.

- Indemnify companies for financial losses sustained as a result of participation.

These steps would create financial carrots for satellite operators while simultaneously lowering risk, incentivizing them to participate. The payments and preferential contract awards that this program would provide can serve as crucial support for many smaller satellite and launch companies; with the US government serving as an anchor client, space companies would have the time and capital they need to grow a civilian client base. That could make the difference between commercial success or failure.

Corporations should participate in the following ways:

- Maintain a significant percentage of satellite constellations capable of providing communications and intelligence-gathering services on short demand to the US military.

- Commit to providing the US government with access to satellite networks if called upon during a conflict or emergency.

Doing so would provide the US military with the resiliency it needs to deter aggression in space, and, should deterrence fail, fight and win.

The US government and corporations should work together in the following ways:

- Create common software and hardware standards to allow communication between government and commercial satellites and receivers.

- Assign specific roles to participating commercial satellites in the event of crisis.

- Conduct military exercises using commercial satellites to improve the efficiency of the system and demonstrate its capabilities to adversaries.

Unlike many other technologies that the military procures, commercial satellites have already proven their utility. The United States should prioritize formalizing its relationship with satellite providers so that, should an emergency arise, the satellites of the civil reserve fleet will be ready to immediately and seamlessly support US warfighters.

Aidan Poling is a research analyst at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. In fall 2022, he was a young global professional in the Forward Defense practice at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Further reading

Thu, Jan 12, 2023

How the US and its allies should respond to evolving space threats

New Atlanticist By

Adversaries are changing the ways they disrupt or destroy US and allied space operations. Our experts give their sense of the latest challenges to security.

Tue, Aug 30, 2022

Commercial satellites are on the front lines of war today. Here’s what this means for the future of warfare.

Airpower after Ukraine By Julia Siegel

Commercial space companies are enabling critical warfighting functions in Ukraine and will continue to provide a lifeline in future conflict scenarios.

Wed, May 18, 2022

Viva la space: Why the commercial small satellite revolution matters for the US government

Event Recap By

A panel of space experts and practitioners discuss with Forward Defense how the US government can leverage commercial small satellite technology to secure the space domain.

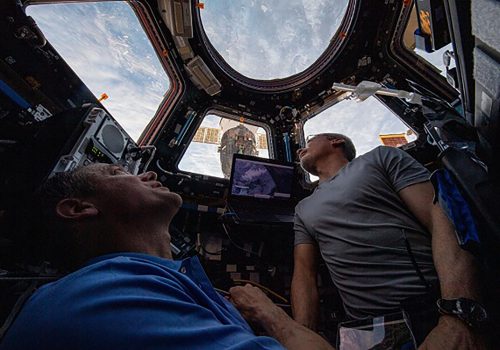

Image: A NASA photo shows a SpaceX Dragon capsule as it is released from the International Space Station in this image released to social media on May 11, 2016. Courtesy NASA/Handout via REUTERS.