The post Ukraine’s invasion of Russia exposes the folly of the West’s escalation fears appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>During the first week of Ukraine’s counter-invasion, Ukrainian forces established control over approximately one thousand square kilometers of land in Russia’s Kursk Oblast, according to Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrsky. This is comparable to the total amount of Ukrainian land seized by Russia since the start of 2024. Ukraine is now moving to establish a military administration over areas of Russia under Kyiv’s control.

Ukraine’s Kursk offensive is a remarkably bold gamble that could prove to be a turning point in the wider war. Defining the strategy and motives behind the operation is a matter for Ukraine’s political and military leadership. However, at this early stage, I believe it is already possible to identify a number of initial successes.

The attack clearly caught the unsuspecting Russians completely off-guard, despite the near ubiquity of surveillance drones on the modern battlefield. This represents a major achievement for Ukraine’s military commanders that has bolstered their already growing international reputation.

Read more coverage of the Kursk offensive

Ukraine’s unexpected offensive has also exposed the weakness of the Putin regime. Throughout his twenty-five year reign, Putin has positioned himself as the strongman ruler of a resurgent military superpower. However, when Russia was invaded for the first time since World War II, it took him days to react. As the BBC reports, he has since avoided using the word “invasion,” speaking instead of “the situation in the border area” or “the events that are taking place,” while deliberately downplaying Ukraine’s offensive by referring to it as “a provocation.”

The response of the once-vaunted Russian military has been equally underwhelming, with large groups of mostly conscript soldiers reportedly surrendering to the rapidly advancing Ukrainians during the first ten days of the invasion. Far from guaranteeing Russia’s security, Putin appears to have left the country unprepared to defend itself.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Ukraine’s dramatic change in tactics comes after almost a year of slow but steady Russian gains in eastern and southern Ukraine. Since 2023, Russian commanders have been deploying their country’s overwhelming manpower and firepower advantages to gradually pummel Ukrainian forces into submission. The Kremlin’s reliance on brute force has proved costly but effective, leaving the Ukrainian military with little choice but to think outside the box.

It has long been obvious that fighting a war of attrition is a losing strategy for Ukraine. The country’s military leaders cannot hope to compete with Russia’s far larger resources and have no desire to match the Kremlin’s disregard for casualties. The Kursk offensive is an attempt to break out of this suffocating situation by returning to a war of mobility and maneuver that favors the more agile and innovative Ukrainian military. So far, it seems to be working.

While bringing Vladimir Putin’s invasion home to Russia has undeniable strategic and emotional appeal, many commentators have questioned why Ukraine would want to occupy Russian territory. The most obvious explanation is that Kyiv seeks bargaining chips to exchange for Russian-occupied Ukrainian lands during future negotiations.

The significant quantity of Russian POWs captured during the offensive also opens up possibilities to bring more imprisoned Ukrainian soldiers home. Meanwhile, control over swathes of Kursk Oblast could make it possible to disrupt the logistical chains supplying the Russian army in Ukraine.

Eurasia Center events

Beyond the military practicalities of the battlefield, the Kursk offensive is challenging some of the most fundamental assumptions about the war. Crucially, Ukraine’s invasion of Russia has demonstrated that Putin’s nuclear threats and his talk of red lines are in reality a big bluff designed to intimidate the West.

Ukrainians have long accused Western policymakers of being overly concerned about the dangers of provoking Putin. They argue that since 2022, the international response to Russian aggression has been hampered by a widespread fear of escalation that has led to regular delays in military aid and absurd restrictions on the use of Western weapons. Ukraine’s offensive has now made a mockery of this excessive caution. If the Kremlin does not view the actual invasion of Russia by a foreign army as worthy of a major escalation, it is hard to imagine what would qualify.

As the Kursk offensive unfolds, Ukraine is hoping the country’s allies will draw the logical conclusions. Initial indications are encouraging, with US and EU officials voicing their support for Ukraine’s cross-border incursion despite longstanding concerns over any military operations inside Russia. At the same time, restrictions on the use of certain categories of weapons remain in place. This is hindering the advance of Ukrainian troops in Kursk Oblast. It is also preventing Kyiv from striking back against the airbases used to bomb Ukrainian cities and the country’s civilian infrastructure.

Ukraine’s Kursk offensive represents a powerful signal to the country’s partners. It demonstrates that the Ukrainian military is a highly professional force capable of conducting complex offensive operations and worthy of greater international backing. It also confirms that Putin’s Russia is dangerously overstretched and is militarily far weaker than it pretends to be.

The muddled and unconvincing Russian response to Ukraine’s invasion speaks volumes about the relative powerlessness of the Putin regime. This should persuade Kyiv’s allies of the need for greater boldness and convince them that the time has come to commit to Ukrainian victory.

Oleksiy Goncharenko is a Ukrainian member of parliament with the European Solidarity party.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post Ukraine’s invasion of Russia exposes the folly of the West’s escalation fears appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Ukraine’s Kursk offensive proves surprise is still possible in modern war appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The Ukrainian military’s ability to maintain a veil of secrecy around preparations for the current operation is all the more remarkable given the evidence from the first two-and-a-half years of Russia’s invasion. The war in Ukraine has been marked by the growing importance of drone and electromagnetic surveillance, creating what most analysts agree is a remarkably transparent battlefield. This is making it more and more difficult for either army to benefit from the element of surprise.

Given the increased visibility on both sides of the front lines, how did Ukraine manage to spring such a surprise? At this stage there is very little detailed information available about Ukraine’s preparations, but initial reports indicate that unprecedented levels of operational silence and the innovative deployment of Ukraine’s electronic warfare capabilities played important roles.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Ukraine’s political leaders have been unusually tight-lipped about the entire offensive, providing no hint in advance and saying very little during the first week of the campaign. This is in stark contrast to the approach adopted last year, when the country’s coming summer offensive was widely referenced by officials and previewed in the media. Ukraine’s efforts to enforce operational silence appear to have also extended to the military. According to The New York Times, even senior Ukrainian commanders only learned of the plan to invade Russia at the last moment.

Ukraine’s Kursk offensive appears to have been a major surprise for Ukraine’s Western partners. The Financial Times has reported that neither the US nor Germany were informed in advance of the planned Ukrainian operation. Given the West’s record of seeking to avoid any actions that might provoke Putin, it is certainly not difficult to understand why Kyiv might have chosen not to signal its intentions.

Read more coverage of the Kursk offensive

This approach seems to have worked. In recent days, the US, Germany, and the EU have all indicated their support for the Ukrainian operation. If Ukraine did indeed proceed without receiving a prior green light from the country’s partners, planners in Kyiv were likely counting on the reluctance of Western leaders to scupper Ukrainian offensive actions at a time when Russia is destroying entire towns and villages as it continues to slowly but steadily advance in eastern Ukraine.

Ukraine’s expanding electronic warfare capabilities are believed to have been instrumental in safeguarding the element of surprise during preparations for the current campaign. The Ukrainian military appears to have succeeded in suppressing Russian surveillance and communications systems across the initial invasion zone via the targeted application of electronic warfare tools. This made it possible to prevent Russian forces from correctly identifying Ukraine’s military build-up or anticipating the coming attack until it was too late.

Eurasia Center events

It is also likely that Ukraine benefited from Russia’s own complacency and overconfidence. Despite suffering a series of defeats in Ukraine since 2022, the Kremlin remains almost pathologically dismissive of Ukrainian capabilities and does not appear to have seriously entertained the possibility of a large-scale Ukrainian invasion of the Russian Federation. The modest defenses established throughout the border zone confirm that Moscow anticipated minor border raids but had no plans to repel a major Ukrainian incursion.

Russia’s sense of confidence doubtless owed much to Western restrictions imposed on Ukraine since the start of the war that have prohibited the use of Western weapons inside Russia. These restrictions were partially relaxed in May 2024 following Russia’s own cross-border offensive into Ukraine’s Kharkiv Oblast, but the Kremlin clearly did not believe Kyiv would be bold enough to use this as the basis for offensive operations inside Russia. Vladimir Putin is now paying a steep price for underestimating his opponent.

It remains far too early to assess the impact of Ukraine’s surprise summer offensive. One of the most interesting questions will be whether Ukraine can force the Kremlin to divert military units from the fighting in eastern Ukraine in order to defend Russia itself. Much will depend on the amount of Russian land Ukraine is able to seize and hold. Putin must also decide whether his military should focus on merely stopping Ukraine’s advance or liberating occupied Russian territory.

Ukraine’s Kursk offensive has succeeded in demonstrating that surprise is still possible on the modern battlefield. This is a significant achievement that underlines the skill and competence of the Ukrainian military. The Ukrainian invasion has also confirmed once again that Putin’s talk of Russian red lines and his frequent threats of nuclear escalation are a bluff designed to intimidate the West. Taken together, these factors should be enough to convince Kyiv’s partners that now is the time to increase military support and provide Ukraine with the tools for victory.

Mykola Bielieskov is a research fellow at the National Institute for Strategic Studies and a senior analyst at Ukrainian NGO “Come Back Alive.” The views expressed in this article are the author’s personal position and do not reflect the opinions or views of NISS or Come Back Alive.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post Ukraine’s Kursk offensive proves surprise is still possible in modern war appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Ukraine continues to expand drone bombing campaign inside Russia appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>This progress has come as no surprise: Ukrainian military planners have been working to capitalize on Russia’s air defense vulnerabilities from the first year of the full-scale invasion. Ukraine’s attacks have escalated significantly since the beginning of 2024, with oil refineries and airfields emerging as the priority targets.

In a July interview with Britain’s Guardian newspaper, Ukrainian commander-in-chief Oleksandr Syrskyi confirmed that Ukrainian drones had hit around two hundred sites connected to Russia’s war machine. Meanwhile, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has vowed to continue increasing the quality and quantity of Ukraine’s long-range drone fleet. Underlining the importance of drones to the Ukrainian war effort, Ukraine recently became the first country in the world to launch a new branch of the military dedicated to drone warfare.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Long-range attack drones are a good fit for Ukraine’s limited offensive capabilities. Kyiv needs to be able to strike military targets inside Russia, but is prevented from doing do with Western-supplied missiles due to restrictions imposed by the country’s partners. While Ukraine has some capacity to produce its own missiles domestically, this is insufficient for a sustained bombing campaign.

Drones are enabling Ukraine to overcome these obstacles. Ukrainian drone production has expanded dramatically over the past two-and-a-half years. The low cost of manufacturing a long-range drone relative to the damage it can cause to Russian military and industrial facilities makes it in many ways the ideal weapon for a cash-strapped but innovative nation like Ukraine.

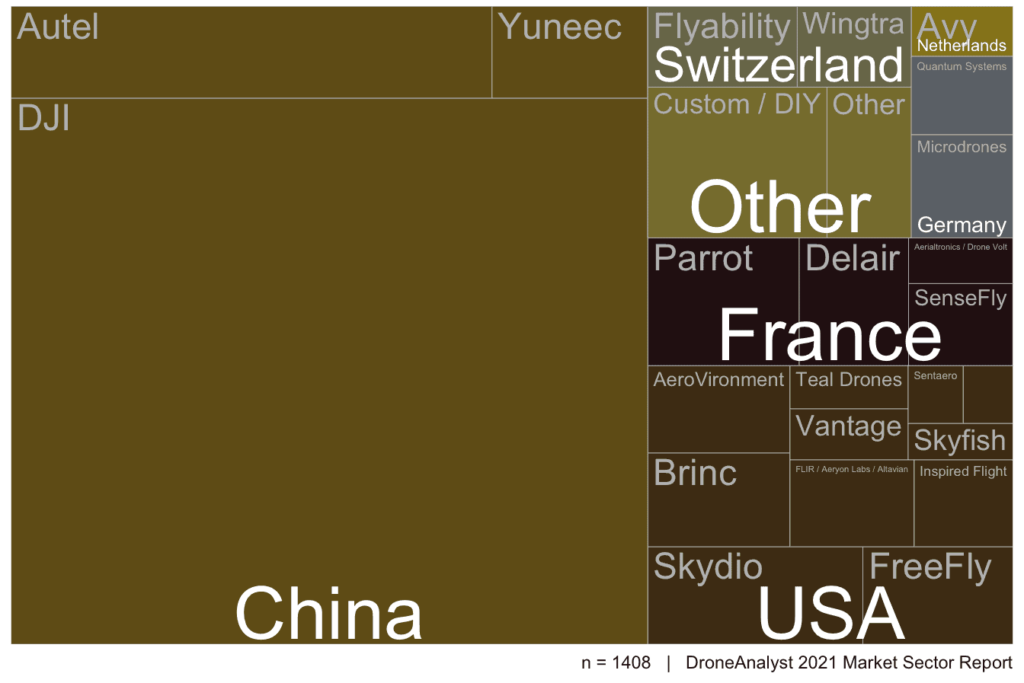

Ukraine’s drone industry is a diverse ecosystem featuring hundreds of participating companies producing different models. The Ukrainian military has used a variety of drones with different characteristics for attacks inside Russia, making the campaign even more challenging for Russia’s air defenses.

The decentralized nature of Ukraine’s drone manufacturing sector also makes it difficult for Russia to target. Even if the Kremlin is able to identify and hit individual production sites located across Ukraine, this is unlikely to have a major impact on the country’s overall output.

Since 2022, Ukraine has taken a number of steps to reduce bureaucracy and streamline cooperation between drone makers and the military. The result is a sector capable of adapting to changing battlefield conditions and able to implement innovations quickly and effectively. This includes efforts to create AI-enabled drones capable of functioning without an operator, making it far more difficult for Russia to jam.

Eurasia Center events

As it expands, Ukraine’s drone bombing campaign is exposing the weaknesses of Russia’s air defenses. Defending a territory as vast as Russia against air strikes would be problematic even in peacetime. With much of Russia’s existing air defense systems currently deployed along the front lines in Ukraine, there are now far fewer systems available to protect industrial and military targets inside Russia.

During the initial stages of the war, this shortage of air defense coverage was not a major issue. However, Ukraine’s broadening bombing offensive is now forcing Russia to make tough decisions regarding the distribution of its limited air defenses.

In addition to strategically important sites such as airbases, the Kremlin must also defend prestige targets from possible attack. In July, CNN reported that air defenses had been significantly strengthened around Russian President Vladimir Putin’s summer residence. Protecting Putin’s palace from attack is necessary to avoid embarrassment, but it means leaving other potential targets exposed.

Ukraine’s drone program is the biggest success story to emerge from the country’s vibrant defense tech sector, and is helping Ukraine to even out the odds against its far larger and wealthier adversary. The country’s partners clearly recognize the importance of drones for the Ukrainian military, and have formed a drone coalition to increase the supply of drones from abroad. This combination of international support and Ukrainian ingenuity spells trouble for Russia. It will likely lead to increasingly powerful and plentiful long-range strikes in the months ahead.

Marcel Plichta is a PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews and former analyst at the US Department of Defense. He has written on the use of drones in the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the Atlantic Council, the Telegraph, and the Spectator.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post Ukraine continues to expand drone bombing campaign inside Russia appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post F-16 jets will help defend Ukrainian cities from Russian bombardment appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>Ukraine’s efforts to persuade partner countries focused on the US, which had to grant permission as the manufacturer of F-16s. Ukrainian pilot Andriy Pilschikov deserves a special mention for the key role he played in the campaign to win American backing. A fluent English speaker and experienced air force pilot known to many by his callsign “Juice,” Pilschikov became the unofficial public face of Ukraine’s appeal for F-16s. Crucially, he was able to articulate why the F-16 was the best choice for Ukraine, arguing that it was the most widely available modern jet and relatively easy to use.

In the initial months of Russia’s full-scale invasion, there was no consensus over which aircraft Ukraine should request from the country’s allies. Various Ukrainian government officials mentioned a range of different models, leading to some confusion. Pilschikov provided much-needed clarity and managed to convince everyone to focus their efforts specifically on the F-16. With support from Ukrainian civil society, he personally travelled to the US and established productive relationships with a number of US officials and members of Congress.

US President Joe Biden finally gave the green light to supply Ukraine with F-16s in summer 2023. However, it would take another year before the the Ukrainian Air Force received the first batch of jets. Sadly, Pilschikov did not live to see this historic day. The pilot who did so much to secure F-16s for his country was killed in a mid-air collision during a training exercise in August 2023.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Despite achieving a breakthrough in summer 2023, the process of preparing for the delivery of F-16s to Ukraine proved frustratingly slow. Ukrainian pilots spent many months training, with only a limited number of slots made available. As a result, Ukraine still has very few pilots able to fly F-16s. Identifying and upgrading Ukrainian airfields capable of accommodating F-16s also created challenges.

The planes that Ukraine has received from the country’s European partners are from the older generation, which is being phased out elsewhere as air forces transition to more modern models. This imposes some limitations on the functions Ukraine’s F-16 fleet can perform. Limited radar reach means that deployment of F-16s on the front lines of the war is seen as too risky, as they could be shot down by both Russian aircraft and Russian air defenses.

Eurasia Center events

With a combat role unlikely at this stage, Ukrainian F-16s will primarily be used to strengthen the country’s air defenses. The planes Kyiv has received are ideally suited to the task of shooting down the Russian missiles and drones that are regularly fired at Ukrainian cities and vital infrastructure.

Their effectiveness in this role will depend on the kinds of missiles they are armed with. F-16s can carry a range of armaments that are more advanced that the types of weapons used by the majority of planes in service with the Russian Air Force. Initial indications are encouraging, with the first F-16s arriving in Ukraine complete with weapons ideally suited to air defense. It is now vital for Ukrainian officials and members of civil society to focus their advocacy efforts on securing sufficient numbers of missiles from partner countries.

Ukraine should also prioritize the supply of long-range radar detection aircraft, such as the planes recently promised by Sweden. In May 2024, the Swedes announced plans to deliver two surveillance aircraft as part of the Scandinavian nation’s largest support package to date. These “eyes in the sky” can monitor airspace for hundreds of kilometers. Together with Ukraine’s growing F-16 fleet, they will significantly enhance the country’s air defenses.

As Ukraine acquires more F-16s in the coming months, and as the country’s limited pool of pilots grows in size and experience, we will likely see these jets used in more adventurous ways. This may include targeting Russian planes and helicopters operating close to the front lines with long-range strikes. For now, though, the main task of Ukraine’s F-16s will be to improve the country’s air defenses and protect the civilian population from Russian bombardment.

Olena Tregub is Executive Director of the Independent Anti-Corruption Commission (NAKO), a member of the Anti-Corruption Council under the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post F-16 jets will help defend Ukrainian cities from Russian bombardment appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Sailing through the spyglass: The strategic advantages of blue OSINT, ubiquitous sensor networks, and deception appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>Open-source intelligence (OSINT) refers to intelligence derived exclusively from publicly or commercially available information that addresses specific intelligence priorities, requirements, or gaps. OSINT encompasses a wide range of sources, including public records, news media, libraries, social media platforms, images, videos, websites, and even the dark web. Commercial technical collection and imagery satellites also provide valuable open-source data. The power of OSINT lies in its ability to provide meaningful, actionable intelligence from diverse and readily available sources.

Thanks to technological advances, OSINT can provide early warning signs of a conflict to come long before it actually breaks out. On land, the proliferation of inexpensive and ubiquitous sensor networks has rendered battlefields almost transparent, making surprise maneuvers more difficult. Through open-source data from smartphones and satellites, persistent OSINT provides early warning of mobilization and other key indicators of military maneuvers. This capability is further augmented by artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced reconnaissance and real-time data analysis, which have proven remarkably effective in modern conflicts including in Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Gaza and Israel, and Sudan. As this paradigm extends to maritime operations, it brings unique challenges and characteristics compared to land operations.

As technology races forward, Blue OSINT stands out as a key tool in the arsenal of contemporary naval warfare during global great-power competition. Blue OSINT harnesses data from commercial satellites, social media, and other publicly available sources to specifically enhance maritime domain awareness, identify emerging threats, and inform strategic decisions.

The current state of Blue OSINT across the spectrum of conflict points to an accelerating technology-driven evolution enabling maritime security and sea-control missions. The US Navy (USN) can enhance Blue OSINT collection with its own commercially procured sensor networks and bespoke uncrewed systems to shape operational environments, prevent and resolve conflicts, and ensure accessibility of sea lines of communications.

Commercially procured sensors span a wide array of technologies, including sonar and acoustic sensors, as well as video and seismic devices that are utilized to detect activities in strategic locations. These sensors can function independently or operate from uncrewed systems, providing flexibility and adaptability in various maritime operations. For instance, uncrewed aerial systems (UAS) equipped with high-resolution cameras and radar can deliver persistent surveillance over expansive oceanic areas, while uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs) with sonar capabilities can monitor subsea activities, such as submarine movements and underwater installations. These uncrewed platforms enable the continuous collection of critical data, enhancing the Navy’s situational awareness and operational readiness without putting sailors at risk.

For the US Navy to best support the joint force and maintain its strategic edge, it must integrate ubiquitous sensor networks and Blue OSINT into naval strategies adapted for tomorrow’s increasingly complex maritime environment. The Navy’s multiyear Project Overmatch is a good start to developing its “network of networks” and contributing to the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) program.

With escalating tensions in the South China Sea, conventional forces are stretched thin and face asymmetric threats such as the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)’s undersea sensing arrays and China’s maritime militia forces. Integrating Blue OSINT and sensor networks into the Navy’s strategies complements traditional naval power, while allowing intelligence missions to be conducted at lower risk and cost. Moreover, the open-source nature of this information enhances the Navy’s ability to share information and collaborate with allies and partners while bypassing cumbersome security classification issues. By relying on easily shareable information, the Navy can better synchronize efforts with partner navies, making command of the sea a more coordinated and viable endeavor.

The impact of evolving open-source intelligence on warfare

| Feature | OSINT | Traditional Intelligence |

|---|---|---|

| Source of data | Commercial satellites, social media, public sources | HUMINT, SIGINT, classified sources |

| Coverage | Global, real-time updates, highly accessible | Selective, based on specific operational requirements |

| Cost | Low cost, leveraging existing commercial infrastructure | High cost, involving extensive human and technical resources |

| Risk | Low risk, minimal direct exposure | Higher risk, involves clandestine operations |

| Data volume | Extremely high, necessitates AI and advanced analytics | Moderate to high, manageable with traditional methods |

| Ease of sharing | High, fewer classification issues | Low, often restricted by security classifications |

| Data warning | Effective, provides pre-conflict indicators | Effective, but often limited by operational scope |

| Deception tactics | Requires advanced techniques to counteract | Relies on traditional counterintelligence and technical methods |

| Collaboration | Enhances collaboration with allies using open data | Limited, restricted sharing due to classification |

| Operational impact | Supports continuous monitoring and quick response | Supports deep, targeted insights into adversaries |

The table above provides a comparison between OSINT and traditional intelligence methods, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. OSINT offers global, real-time updates at a lower cost by leveraging existing commercial infrastructure. This approach presents a lower risk, as it involves minimal direct exposure and facilitates easier information sharing due to fewer classification issues.

On the other hand, traditional intelligence methods such as human intelligence (HUMINT) and signals intelligence (SIGINT) provide selective, targeted insights based on specific operational requirements. These methods often involve higher costs and risks due to the need for extensive human and technical resources, as well as the nature of clandestine operations. While traditional intelligence can offer deep, targeted insights, it is often limited by operational scope and security classification issues, making information sharing more challenging.

In the maritime domain, these distinctions are particularly significant. The concept of Blue OSINT integrates these principles specifically for naval operations, emphasizing the need for continuous monitoring and rapid-response capabilities.

Blue OSINT and persistent maritime monitoring

In the pre-conflict stage, global satellite coverage and social media provide a wealth of data that can map maritime activity with unprecedented detail. Nonprofit organizations like Global Fishing Watch use commercial satellite constellations to track ships and monitor maritime activity. Increased affordability and accessibility of satellite technology have enabled nongovernmental and commercial entities to contribute to maritime domain awareness in new ways. For instance, maritime radar emissions—once the exclusive domain of military and intelligence satellites—are now easily observable and “tweetable,” allowing for vessel identification to be accomplished more easily when actors execute deceptive techniques. Similarly, platforms like X (formerly Twitter) host numerous “ship spotting” accounts, where enthusiasts post photos and updates of vessels passing through strategic chokepoints and major straits, further enriching the available data.

Through persistent monitoring and large-scale data analysis, Blue OSINT can be used to significantly mitigate the challenge of monitoring large exclusive economic zones (EEZs). It offers a cost-effective alternative to traditional patrols, allowing these navies to adopt a more targeted approach when deploying their limited resources. By embracing Blue OSINT, naval forces can enhance their surveillance and response capabilities without a heavy financial burden, ensuring that these forces remain agile and effective in their maritime operations. Additionally, data streams from ubiquitous sensor networks can be coupled with Blue OSINT collection to give naval intelligence experts near-endless amounts of data in support of complex reconnaissance operations, without placing sailors and special operators at increased risk to collect it.

In addition to myriad opportunities for intelligence collection, using Blue OSINT presents technological challenges for the US Navy. The sheer volume of data generated by ubiquitous sensor networks and Blue OSINT tools necessitate substantial investments in software and analytic tools to manage and interpret this information effectively. Intelligence professionals must sift through endless amounts of data to identify actionable insights. Even the most skilled analysts need software and computer processing that can help organize and parse raw data.

To address these challenges, the US Navy and other maritime forces are ramping up investments in commercially procured sensor networks and cutting-edge analytic tools. In June 2024, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency issued its first-ever commercial solicitation for unclassified technology to help track illicit fishing in the Pacific. Such investments aim to access, exploit, and process the massive amounts of data generated, a key step to achieving comprehensive maritime domain awareness. Better software and analytic tools can help maximize the potential of Blue OSINT and sensor networks, ensuring that intelligence analysts can better inform decision-makers at the speed of relevance.

Strategic deployment of distributed sensors

While Blue OSINT provides valuable insights into chokepoints and shipping lanes, it does not yet offer comprehensive coverage of the open ocean. Its effectiveness is greater in populated and coastal areas, where the density of electronic devices and human activity is significantly higher than on the high seas. Moreover, OSINT data can often be easily manipulated, presenting challenges in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the information gathered. For example, although ships emitting Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals can be tracked on the web, navies are aware that bad actors often tamper with their transponders in order to disguise their locations, ultimately limiting the signals’ reliability.

To bypass these limitations of open-source data, navies and intelligence agencies can enhance their Blue OSINT capabilities by augmenting them with strategically deployed clandestine sensor networks in key locations, such as harbors, straits, and other critical chokepoints. This combination of data flows allows for effective monitoring and data collection on vessel movements, communications, and adversary intentions. Additionally, other covert sensors can be hidden on the seabed or disguised on civilian vessels, like fishing boats, in regions such as the South China Sea. Using distributed sensors along with Blue OSINT data ensures continuous and comprehensive maritime situational awareness, even in areas less frequented by military assets.

However, fixed sensor networks alone are insufficient to cover the dynamic maritime environment. Deploying a mobile network of distributed sensors necessitates a diverse array of platforms and technologies. While military satellites, ships, and aircraft equipped with advanced sensors can offer intermittent coverage, they are costly and limited in number, and their findings are less easily shareable with partners and allies. To bridge these gaps, allied navies should invest in affordable and scalable solutions such as uncrewed surface vehicles (USVs), UUVs, and UASs. Outfitted with various sensors, these platforms can effectively detect and track adversary movements, ensuring that navies maintain situational awareness across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean and other critical regions.

Small UASs launched from naval ships can be used to rapidly surveil large swaths of sea, providing real-time data on both surface and subsurface activities. Recognizing the strategic advantage of uncrewed systems, China has taken a bold step to outpace the US Navy by developing an aircraft carrier specifically designed to launch and recover UASs, rather than sophisticated manned platforms like the J-20 fighter jet. This significant investment in a carrier solely for uncrewed vehicles by the PLAN should prompt the United States to reconsider, and potentially adjust, its future resourcing strategy. Similarly, USVs can conduct long-duration patrols at a fraction of the cost of manned ship operations, exemplified by Saildrone vessels patrolling the Indian Ocean, providing the USN a robust sensor network. UUVs, deployed from submarines or surface ships, can monitor subsea activities, such as the movement of submarines and other submersible assets.

By monitoring the air, sea, and underwater environments, uncrewed vehicles and their sensors can significantly enhance overall maritime situational awareness. However, these tools are only effective if they are integrated into a cohesive architecture that combines traditional intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) with Blue OSINT data and affordable long-term leave-behind sensors. Project Overmatch exemplifies how to achieve this integration by developing a network that links sensors, shooters, and command nodes across all domains. For instance, Project Overmatch aims to leverage advanced data analytics, artificial intelligence, and secure communications to create a unified maritime operational picture, enabling faster and more informed decision-making. By incorporating these elements, the US Navy can ensure that uncrewed vehicles and their sensors are effectively utilized to maintain operational superiority in the maritime domain.

Moreover, the low-signature nature of some of these sensors increases the odds that they can operate undetected by adversaries, providing a strategic advantage. By deploying sensors in unexpected locations, and disguising them as civilian assets in some cases, navies can gather intelligence without alerting potential threats to their presence.

Blue OSINT and sensor networks in conflict

While Blue OSINT collection and distributed sensor networks can easily collect data in uncontested waters, they have immediate applications to modern maritime conflict as well. For instance, in the event of a cross-strait invasion by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the transparency provided by Blue OSINT would make it difficult for navies to maneuver undetected. Satellites and social media continuously monitor naval piers, strategic chokepoints, and even some open ocean areas, making it increasingly difficult to achieve tactical surprise. Historical instances—such as Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the D-Day invasion, or the successful surprise dash to transit the English Channel by the German fleet during World War II—would be much harder to achieve in the modern era due to the pervasive nature of Blue OSINT.

In the context of a potential Taiwan invasion, Blue OSINT would likely be used to detect and closely follow Chinese naval activities, including the movement of amphibious assault ships and submarines. OSINT analysts frequently examine satellite imagery of Chinese shipyards and military installations, which could provide early indications of mobilization.

However, relying solely on satellite imagery and AIS for Blue OSINT is insufficient. Multi-intelligence capabilities are essential to provide a comprehensive assessment. For instance, in 2020, two commercial firms collaborated to use radio frequency and synthetic aperture radar collection to detect Chinese illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing near the Galapagos EEZ. This open-source technique revealed the ability to identify fishing vessels that turned off their AIS to cross into the EEZ. In a future conflict with China, the same methodology of combining multiple Blue OSINT sources could be used to identify and track vessels of the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). This would bypass the AIS vulnerabilities that the PAFMM traditionally exploits to avoid detection, while also revealing its intentions as directed by the PLAN.

The Russo-Ukraine conflict revealed how OSINT can thwart surprise maneuvers and provide crucial targeting data deep behind enemy lines. However, it also underscores the limitations of OSINT in sparsely populated environments, such as the open ocean. For example, in December 2023, as missiles flew over the Red Sea, 18 percent of global container-ship capacity was rerouted. While civilian mariners and commercial shipping significantly contribute to Blue OSINT during peacetime, their absence in a high-risk conflict scenario would shift the burden more heavily onto satellite and uncrewed systems.

Deception and stealth

While the US Navy can take advantage of these technologies, its adversaries can, and almost certainly will, do the same. The US Navy and its allies must develop countermeasures to mitigate the risks posed by sensor networks while also leveraging its benefits. One approach is to invest in advanced deception tactics designed to mislead adversaries. These include the use of decoys, electronic warfare, and signal spoofing to create false targets and confuse enemy sensors. The Navy has been quietly developing these tools to obscure its true movements and intentions, ultimately confounding adversaries and making it harder for them to accurately target US forces.

In addition to deception, the United States and its allies need to enhance their naval stealth capabilities to evade adversaries’ distributed sensor networks. This involves not only minimizing the electromagnetic signatures of their vessels, but also employing innovative designs and operational tactics to reduce their radar cross-sections and avoid detection.

Distributed sensors in conflict

The ability to complement Blue OSINT with distributed sensors will be a decisive factor in near-term conflict dynamics. Just as frontline units in Ukraine are detected and targeted by cheap drones and stationary sensors, naval forces can be identified and pinpointed by similar systems at sea. Distributed sensors can provide continuous monitoring and data collection, ensuring that navies can maintain situational awareness and respond swiftly to emerging threats.

Three pillars are necessary to distribute sensors effectively across the ocean.

First, large conventional fleets play a critical role in maritime strategy. These fleets must be capable of extended operations and diverse missions, providing the backbone of naval presence, power projection, sea lines of communication, and, ultimately, sea control. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the US Navy demonstrated its endurance with record-length deployments, showcasing an advantage that could be significant in future maritime campaigns.

Second, organic reconnaissance drones are essential. Each destroyer and aircraft carrier should be equipped with its own fleet of multi-domain drones to conduct surveillance and gather intelligence. Currently, US carrier strike groups rely on land-launched surveillance drones, which are vulnerable and limited in number. Integrating organic drones into each vessel would enhance situational awareness and operational flexibility, allowing for more effective and autonomous intelligence-gathering capabilities.

Third, large fleets of affordable USVs and UUVs can deploy sensors across the ocean, increasing sensor hours at sea and improving maritime domain awareness. The first Replicator tranche is equipping forces with thousands of attritable systems to turn the Taiwan Strait into “an unmanned hellscape,” demonstrating the strategic value of uncrewed systems in contested waters. Moreover, the Navy is experimenting with diverse types of uncrewed platforms, aiming to create a distributed fleet architecture that is even more lethal than today’s carrier-centric fleet. These unmanned systems provide a cost-effective means to enhance surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities across vast oceanic areas, ensuring that the Navy can maintain a strategic advantage in both peacetime and conflict scenarios.

Recommendations

To maximize the efficacy of maritime domain awareness, it is crucial to integrate data from both Blue OSINT and ubiquitous sensor networks. While these two systems of data collection are largely distinct, their combined use can significantly enhance the accuracy and comprehensiveness of intelligence assessments and naval warfare.

- Leverage Blue OSINT. Significant investment in artificial intelligence and advanced analytics is necessary to manage and interpret the endless amounts of data generated by open-source intelligence. By fostering a coordinated approach to maritime security, Blue OSINT can facilitate easier information sharing with allies and partners, but only if its utilization is preplanned. Collaborative pathways for Blue OSINT data collection, processing, and analysis must take shape early in the concept and planning phases. This collaborative effort will significantly enhance collective situational awareness and operational effectiveness, making it easier for navies to synchronize their efforts. Additionally, complementing Blue OSINT with traditional intelligence collection such as HUMINT and SIGINT provides a comprehensive threat assessment. By integrating these capabilities, navies can more easily attain a well-rounded understanding of adversary actions.

- Commercially procure distributed sensing capabilities and networks. The US Navy must invest in Replicator-style unmanned platforms that can affordably deploy sensors across maritime battlefields, similar to the use of small UAS for land reconnaissance. These commercially procured distributed sensing platforms will significantly enhance the Navy’s ability to continuously and comprehensively monitor vast areas, improving overall maritime domain awareness.

- Recognize a new maritime operating environment. The US Navy must prepare for protracted missions away from easily monitored ports and chokepoints while penetrating adversary-controlled, denied waters. This mission set requires a robust logistical framework capable of supporting extended deployments in remote and contested waters. By developing sophisticated tactics to deceive and confuse distributed sensor networks, the Navy can minimize its visibility to adversaries and maintain strategic surprise. This necessitates investing in advanced deception technologies such as electronic warfare, signal spoofing, and decoys to create false targets and obscure true movements. Additionally, enhancing the stealth capabilities of vessels through innovative designs and operational practices will further ensure that naval forces can evade detection and operate effectively in a sensor-saturated environment. By embracing these realities, the Navy can sustain its operational effectiveness and strategic advantage across the competition continuum.

Conclusion

In an era of distributed sensing networks and Blue OSINT, adaptation is not just about leveraging technology but also about evolving operational doctrines to meet the challenges of contemporary maritime conflicts. By integrating Blue OSINT capabilities, deploying distributed sensors, and countering (and employing) deception, naval forces can maintain an asymmetric advantage in the increasingly visible and contested maritime domain.

The success of modern naval operations hinges on the ability to swiftly adapt to technological advancements and evolving threats. Navies must transcend beyond traditional methods and embrace innovative strategies to remain agile and effective. This demands a concerted effort from all levels of naval leadership, from policymakers to forward operators, to implement these changes.

On the unforgiving sea, only those who rapidly transform to the era of Blue OSINT will avoid the abyss, with the rest risk sinking into obsolescence as adversaries gain decisional advantage. Navies that fail to adjust to the realities of Blue OSINT and sensor networks risk ending up like the Russian Black Sea Fleet: at the bottom of the ocean.

Authors

Guido L. Torres is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Forward Defense Program and the executive director of the Irregular Warfare Initiative.

Austin Gray is co-founder and chief strategy officer of Blue Water Autonomy. He previously worked in a Ukrainian drone factory and served in US naval intelligence.

Related content

Forward Defense, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, generates ideas and connects stakeholders in the defense ecosystem to promote an enduring military advantage for the United States, its allies, and partners. Our work identifies the defense strategies, capabilities, and resources the United States needs to deter and, if necessary, prevail in future conflict.

The post Sailing through the spyglass: The strategic advantages of blue OSINT, ubiquitous sensor networks, and deception appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Ukraine’s new F-16 jets won’t defeat Russia but will enhance air defenses appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>US President Joe Biden confirmed his support for the supply of F-16s in August 2023, but subsequent progress was slow. Training for Ukrainian pilots and ground crews has taken up to nine months, with an already technically complex and demanding process reportedly further complicated by language barriers. There have also been significant obstacles to identifying and preparing Ukrainian airbases with suitable facilities and adequate defenses.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

The F-16 models that Ukraine has now begun to receive are a clear step up from the Soviet-era jets inherited from the USSR, boasting superior radar capabilities and longer range. At the same time, Ukraine’s F-16s should not be viewed as a game-changing weapon in the war with Russia.

One obvious issue is quantity. Ukraine has so far only received a handful of F-16s, with a total of 24 jets expected to arrive by the end of 2024. To put this number into context, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has stated in recent weeks that in order to effectively counter Russian air power, his country would require a fleet of 128 F-16 jets. So far, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands have committed to supply Ukraine with eighty F-16s, but there is no clear time frame for deliveries or for the training of additional pilots.

Ukraine’s fledgling F-16 fleet will likely have access to a limited selection of weapons, with partner countries currently pledging to provide a number of short-range munitions. It remains unclear whether Kyiv can count on longer range strike capabilities, despite recent reports that the US has agreed to arm Ukrainian F-16s with American-made missiles and other advanced weapons. The effectiveness of Ukraine’s new jets will also be constrained by restrictions on the use of Western weapons against targets inside Russia.

The limited number of F-16s in Ukraine means that these new arrivals will initially be deployed primarily to strengthen the country’s air defenses. The jets will considerably enhance Ukraine’s ability to prevent Russian pilots entering Ukrainian air space, and can also target Russian cruise missiles in flight. This is particularly important as Russia has recently demonstrated its growing ability to bypass existing surface-to-air defense systems and strike civilian infrastructure targets across Ukraine.

Eurasia Center events

Ukraine’s F-16s enter service in what is an extremely challenging operating environment, with Russia’s sophisticated battlefield air defenses likely to make any combat support roles extremely risky. Acknowledging these difficulties, Ukraine’s commander in chief Oleksandr Syrskiy recently stated that the country’s F-16s would operate at a distance of at least forty kilometers from the front.

Another key challenge will be protecting Ukrainian F-16s on the ground against Russian attempts to destroy them with ballistic missiles. The Kremlin has made no secret of the fact that the jets are priority targets that will be hunted with particular enthusiasm. The Ukrainian Air Force will have to adapt quickly in order to counter this threat, and must rely on a combination of Patriot air defenses, decoy F-16s, and frequent airfield changes.

While the long-awaited arrival of F-16s in Ukraine has sparked considerable excitement and provided Ukrainians with a welcome morale boost, these new jets are not a wonder weapon that can change the course of the war. Instead, Ukraine’s small fleet of F-16s will bolster the country’s air defenses, helping to protect Ukrainian cities and critical infrastructure from Russian bombardment.

Over the coming year, Ukraine will face the task of gradually integrating and expanding its F-16 fleet. Based on past experience of Western weapons deliveries, Kyiv can expect to receive additional munitions, and may also eventually be given the green light to strike some categories of military targets inside Russia. This would open up a range of offensive options that could change the battlefield dynamics of the war in Ukraine’s favor. For now, though, the biggest change is likely to be in terms of enhanced security for Ukraine’s civilian population.

Mykola Bielieskov is a research fellow at the National Institute for Strategic Studies and a senior analyst at Ukrainian NGO “Come Back Alive.” The views expressed in this article are the author’s personal position and do not reflect the opinions or views of NISS or Come Back Alive.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post Ukraine’s new F-16 jets won’t defeat Russia but will enhance air defenses appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Ukraine’s drone success offers a blueprint for cybersecurity strategy appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>This and similar incidents have highlighted the importance of the cyber front in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine has invested significant funds in cybersecurity and can call upon an impressive array of international partners. However, the country currently lacks sufficient domestic cybersecurity system manufacturers.

Ukraine’s rapidly expanding drone manufacturing sector may offer the solution. The growth of Ukrainian domestic drone production over the past two and a half years is arguably the country’s most significant defense tech success story since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion. If correctly implemented, it could serve as a model for the creation of a more robust domestic cybersecurity industry.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Speaking in summer 2023, Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation Mykhailo Fedorov outlined the country’s drone strategy of bringing together drone manufacturers and military officials to address problems, approve designs, secure funding, and streamline collaboration. Thanks to this approach, he predicted a one hundred fold increase in output by the end of the year.

The Ukrainian drone production industry began as a volunteer project in the early days of the Russian invasion, and quickly became a nationwide movement. The initial goal was to provide the Ukrainian military with 10,000 FPV (first person view) drones along with ammunition. This was soon replaced by far more ambitious objectives. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, more the one billion US dollars has been collected by Ukrainians via fundraising efforts for the purchase of drones. According to online polls, Ukrainians are more inclined to donate money for drones than any other cause.

Today, Ukrainian drone production has evolved from volunteer effort to national strategic priority. According to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the country will produce more than one million drones in 2024. This includes various types of drone models, not just small FPV drones for targeting personnel and armored vehicles on the battlefield. By early 2024, Ukraine had reportedly caught up with Russia in the production of kamikaze drones similar in characteristics to the large Iranian Shahed drones used by Russia to attack Ukrainian energy infrastructure. This progress owes much to cooperation between state bodies and private manufacturers.

Marine drones are a separate Ukrainian success story. Since February 2022, Ukraine has used domestically developed marine drones to damage or sink around one third of the entire Russian Black Sea Fleet, forcing Putin to withdraw most of his remaining warships from occupied Crimea to the port of Novorossiysk in Russia. New Russian defensive measures are consistently met with upgraded Ukrainian marine drones.

Eurasia Center events

In May 2024, Ukraine became the first country in the world to create an entire branch of the armed forces dedicated to drone warfare. The commander of this new drone branch, Vadym Sukharevsky, has since identified the diversity of country’s drone production as a major asset. As end users, the Ukrainian military is interested in as wide a selection of manufacturers and products as possible. To date, contracts have been signed with more than 125 manufacturers.

The lessons learned from the successful development of Ukraine’s drone manufacturing ecosystem should now be applied to the country’s cybersecurity strategy. “Ukraine has the talent to develop cutting-edge cyber products, but lacks investment. Government support is crucial, as can be seen in the drone industry. Allocating budgets to buy local cybersecurity products will create a thriving market and attract investors. Importing technologies strengthens capabilities but this approach doesn’t build a robust national industry,” commented Oleh Derevianko, co-founder and chairman of Information Systems Security Partners.

The development of Ukraine’s domestic drone capabilities has been so striking because local manufacturers are able to test and refine their products in authentic combat conditions. This allows them to respond on a daily basis to new defensive measures employed by the Russians. The same principle is necessary in cybersecurity. Ukraine regularly faces fresh challenges from Russian cyber forces and hacker groups; the most effective approach would involve developing solutions on-site. Among other things, this would make it possible to conduct immediate tests in genuine wartime conditions, as is done with drones.

At present, Ukraine’s primary cybersecurity funding comes from the Ukrainian defense budget and international donors. These investments would be more effective if one of the conditions was the procurement of some solutions from local Ukrainian companies. Today, only a handful of Ukrainian IT companies supply the Ukrainian authorities with cybersecurity solutions. Increasing this number to at least dozens of companies would create a local industry capable of producing world-class products. As we have seen with the rapid growth of the Ukrainian drone industry, this strategy would likely strengthen Ukraine’s own cyber defenses while also boosting the cybersecurity of the wider Western world.

Anatoly Motkin is president of StrategEast, a non-profit organization with offices in the United States, Ukraine, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan dedicated to developing knowledge-driven economies in the Eurasian region.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post Ukraine’s drone success offers a blueprint for cybersecurity strategy appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Russia’s retreat from Crimea makes a mockery of the West’s escalation fears appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The withdrawal of Russian warships from Crimea is the latest indication that against all odds, Ukraine is actually winning the war at sea. When Russia first began the blockade of Ukraine’s ports on the eve of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, few believed the ramshackle Ukrainian Navy could seriously challenge the dominance of the mighty Russian Black Sea Fleet. Once hostilities were underway, however, it soon became apparent that Ukraine had no intention of conceding control of the Black Sea to Putin without a fight.

Beginning with the April 2022 sinking of the Russian Black Sea Fleet flagship, the Moskva, Ukraine has used a combination of domestically produced drones and missiles together with Western-supplied long-range weapons to strike a series of devastating blows against Putin’s fleet. Cruise missiles delivered by Kyiv’s British and French partners have played an important role in this campaign, but the most potent weapons of all have been Ukraine’s own rapidly evolving fleet of innovative marine drones.

The results speak for themselves. When the full-scale invasion began, the Russian Black Sea Fleet had seventy four warships, most of which were based at ports in Russian-occupied Crimea. In a little over two years, Ukraine managed to sink or damage around one third of these ships. In the second half of 2023, reports were already emerging of Russian warships being hurriedly moved across the Black Sea from Crimea to the relative safety of Novorossiysk in Russia. By March 2024, the Russian Black Sea Fleet had become “functionally inactive,” according to the British Ministry of Defense.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Ukraine’s remarkable success in the Battle of the Black Sea has had significant practical implications for the wider war. It has disrupted Russian logistics and hindered the resupply of Russian troops in southern Ukraine, while limiting Russia’s ability to bomb Ukrainian targets from warships armed with cruise missiles. Crucially, it has also enabled Ukraine to break the blockade the country’s Black Sea ports and resume commercial shipping via a new maritime corridor. As a result, Ukrainian agricultural exports are now close to prewar levels, providing Kyiv with a vital economic lifeline.

The Russian reaction to mounting setbacks in the Battle of the Black Sea has also been extremely revealing, and offers valuable lessons for the future conduct of the war. It has often been suggested that a cornered and beaten Vladimir Putin could potentially resort to the most extreme measures, including the use of nuclear weapons. In fact, he has responded to the humiliating defeat of the Black Sea Fleet by quietly ordering his remaining warships to retreat.

This underwhelming response is all the more telling given the symbolic significance of Crimea to the Putin regime. The Russian invasion of Ukraine first began in spring 2014 with the seizure of Crimea, which occupies an almost mystical position in Russian national folklore as the home of the country’s Black Sea Fleet. Throughout the past decade, the occupied Ukrainian peninsula has featured heavily in Kremlin propaganda trumpeting Russia’s return to Great Power status, and has come to symbolize Putin’s personal claim to a place in Russian history.

Eurasia Center events

Crimea’s elevated status was initially enough to make some of Ukraine’s international partners wary of sanctioning strikes on the occupied peninsula. However, the Ukrainians themselves had no such concerns. Instead, they simply disregarded the Kremlin’s talk of dire consequences and began attacking Russian military targets across Crimea and throughout the Black Sea. More than two years later, these attacks have now become a routine feature of the war and are taken for granted by all sides. Indeed, the Kremlin media plays down attacks on Crimea and largely ignores the frequent sinking of Russian warships, no doubt to save Putin’s blushes.

The Russian Navy’s readiness to retreat from its supposedly sacred home ports in Crimea has made a mockery of Moscow’s so-called red lines and exposed the emptiness of Putin’s nuclear threats. Nevertheless, Kyiv’s international allies remain reluctant to draw the obvious conclusions. Instead, Western support for Ukraine continues to be defined by self-defeating fears of escalation.

For almost two and a half years, Ukraine’s partners have allowed themselves to be intimidated into denying Ukraine certain categories of weapons and restricting attacks inside Russia. This is usually done while piously citing the need to prevent the current conflict from spreading any further. Western policymakers apparently prefer to ignore the overwhelming evidence from the Battle of the Black Sea, which confirms that when confronted by resolute opposition, Putin is far more likely to back down than escalate.

The West’s fear of escalation is Putin’s most effective weapon. It allows him to limit the military aid reaching Kyiv, while also preventing Ukraine from striking back against Russia. This is slowly but surely setting the stage for inevitable Russian victory in a long war of attrition. Western leaders claim to be motivated by a desire to avoid provoking a wider war, but that is exactly what will happen if they continue to pursue misguided policies of escalation management and fail to stop Putin in Ukraine.

Peter Dickinson is editor of the Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert service.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

The post Russia’s retreat from Crimea makes a mockery of the West’s escalation fears appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>The post Modernizing space-based nuclear command, control, and communications appeared first on Atlantic Council.

]]>Table of contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- What is the NC3 system?

- The nature of NC3

- Current NC3 missions and space systems

- How the attributes of space and space systems shape space security

- Geopolitical challenges to the current NC3 system

- Counterspace threats to space-based NC3

- Modernization plans for space-based NC3

- Conclusion and recommendations

- About the authors

- Acknowledgements

If I take nuclear command and control and spread it across 400 satellites … how many satellites do I have to shoot down now to take out the US nuclear command and control?”

Gen. B. Chance Saltzman, Chief of Space Operations (CSO) United States Space Force (USSF)

Abstract

US nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) is a bedrock for nuclear deterrence and the US-led, rules-based international order that it supports. Like the rest of the US nuclear arsenal, NC3 is in the midst of a modernization overhaul. The space-based elements of NC3, however, face different geopolitical, technical, and bureaucratic challenges during this modernization. Geopolitically, the two-nuclear-peer challenge, China’s perception of NC3 and strategic stability, and the prospect of limited nuclear use call into question the sufficiency of existing and next-generation NC3. Technically, Russia and China are developing more sophisticated counterspace weapons, which hold at risk space-based US NC3. Bureaucratically, the US Department of Defense (DOD)’s shift to a proliferated space architecture may not be appropriately prioritizing requirements for systems that are essential for NC3 missions. To address these challenges, space-focused agencies in the DOD need to ensure that nuclear surety is not given short shrift in the future of space systems planning.

Introduction

The NC3 system is one of the most opaque, complex, hardened, least understood, and perhaps least appreciated foundations for nuclear deterrence and strategic stability. While each military service is busy developing and attempting to resource its instantiation of combined joint all domain command and control (CJADC2), NC3 has not yet enjoyed this same focus and attention. As security dynamics and technology developments continue to evolve, the United States must commit appropriate resources and focus to ensure the continuing effectiveness of NC3. In simple terms, NC3 is the protected and assured missile, air, and space warning and communication system enabling the command and control of US nuclear forces that must operate effectively under the most extreme and existentially challenging conditions—employment of nuclear weapons. The 2022 US Nuclear Posture Review explains the five essential functions of NC3: “detection, warning, and attack characterization; adaptive nuclear planning; decision-making conferencing; receiving and executing Presidential orders; and enabling the management and direction of forces.”1

The NC3 system must never permit the use of nuclear weapons unless specifically authorized by the president, the only use-approval authority (negative control), while always enabling their use in the specific ways the president authorizes (positive control). Risk tolerance for NC3 systems is understandably nonexistent; there can be no uncertainty in the ability of the United States to positively command and control its nuclear forces at any given moment. The DOD and Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration use the term “nuclear surety” to describe their comprehensive programs for the safety, security, and control of nuclear weapons that leave no margin for error. The requirement for nuclear surety is constant, but it is becoming more difficult to deliver because threats to US NC3 systems are increasing, due to geopolitical, technical, and bureaucratic trends and developments.

The geopolitical environment has shifted in significant ways since current US NC3 systems were deployed. The space-based elements of NC3 are now threatened in unprecedented ways, due to Chinese and Russian testing and deployment of a range of counterspace capabilities that can hold space-based NC3 systems at risk. As demonstrated by the current war in Ukraine, even regional conflicts can manifest long-standing questions and concerns about NC3 in a multipolar and increasingly complex global security environment. Layer in China’s quantitative and qualitative rise in strategic nuclear weapons delivery systems and the unwillingness of China’s leadership to have basic discussions about strategic stability, and the 1960s architecture that is the foundation of US NC3 systems seems to be growing increasingly inadequate to deal with the geopolitical challenges of today and tomorrow. The reality is that the current NC3 system and architectures were predicated upon a bipolar nuclear geopolitical situation that no longer exists. Today, a multipolar, globally proliferated, and largely unconstrained nuclear weapons environment requires integrated deterrence across domains, sectors, and alliances.

The geopolitical environment has shifted in significant ways since current US NC3 systems were deployed. The space-based elements of NC3 are now threatened in unprecedented ways, due to Chinese and Russian testing and deployment of a range of counterspace capabilities that can hold space-based NC3 systems at risk. As demonstrated by the current war in Ukraine, even regional conflicts can manifest long-standing questions and concerns about NC3 in a multipolar and increasingly complex global security environment. Layer in China’s quantitative and qualitative rise in strategic nuclear weapons delivery systems and the unwillingness of China’s leadership to have basic discussions about strategic stability, and the 1960s architecture that is the foundation of US NC3 systems seems to be growing increasingly inadequate to deal with the geopolitical challenges of today and tomorrow. The reality is that the current NC3 system and architectures were predicated upon a bipolar nuclear geopolitical situation that no longer exists. Today, a multipolar, globally proliferated, and largely unconstrained nuclear weapons environment requires integrated deterrence across domains, sectors, and alliances.

While the geopolitical environment has evolved, so too has the technology available to deliver NC3 capabilities. Many of the current NC3 systems were developed decades ago using analog technology but are now being updated to digital interfaces, switches, and underlying network topologies. This transition will enable enhanced capabilities, but it will also open more threat vectors that can be exploited via various cyber means through all segments of the system. As the space-based systems that are part of the NC3 system are being comprehensively upgraded, whether for missile warning (detecting and characterizing a missile), missile tracking, or delivering persistent assured communications, the DOD must work to eliminate exploitable cyber vulnerabilities and maintain distributed end-to-end network and supply chain security.

Additionally, almost all the DOD’s bureaucratic structures that acquired the current NC3 systems have changed, sometimes in radical ways. Primary responsibility for acquisition of important elements of the NC3 system are now divided between several organizations that are not focused on nuclear surety, making it a significant challenge to achieve effective integration and unity of command and effort across this structure. Moreover, the overall architecture for US space systems is transitioning toward a hybrid approach that uses commercial, international, and government systems and capabilities to enhance space mission assurance. The benefits of this hybrid approach seem clear for most mission areas, but it is not necessarily optimal for NC3. The DOD must ensure that nuclear surety remains a foundational and non-negotiable requirement for next-generation NC3 systems and cannot allow this requirement to be out-prioritized by other important considerations or become adrift in new bureaucratic structures.

Given the importance of the capabilities, evolving geopolitical and technical threats, and the diverse units planning modernization of the system, the United States must think carefully about the best ways to acquire the next-generation, and generation-after-next, of space-based NC3 to continue delivering nuclear surety in a new landscape that is characterized by a breathtaking degree and pace of change, troubling factors which seem likely to persist or even accelerate. The 2022 US Nuclear Posture Review reaffirms the US commitment to modernizing NC3 and lays out key challenges:

We will employ an optimized mix of resilience approaches to protect the next-generation NC3 architecture from threats posed by competitor capabilities. This includes, but is not limited to, enhanced protection from cyber, space-based, and electro-magnetic pulse threats; enhanced integrated tactical warning and attack assessment; improved command post and communication links; advanced decision support technology; and integrated planning and operations.”

2022 Nuclear Posture Review.

This paper characterizes the existing NC3 system and focuses on its space-based missions and elements. It describes how orbital dynamics shape space security and examines the emerging geopolitical, technical, and bureaucratic challenges to the extant NC3 system. Finally, it analyzes how ongoing modernization programs are addressing these challenges and offers some recommendations.

What is the NC3 system?

The nature of NC3

Department of the Air Force (DAF) doctrine defines the NC3 system as “the means through which Presidential authority is exercised and operational command control of nuclear operations is conducted. The NC3 system is part of the larger national leadership command capability (NLCC), which encompasses the three broad mission areas of: (1) Presidential and senior leader communications; (2) NC3; (3) and continuity of operations and government communications.”2

The current NC3 architecture is comprised of two separate but interrelated layers. The DOD’s 2020 Nuclear Matters Handbook describes it as follows:

The first layer is the day-to-day architecture which includes a variety of facilities and communications to provide robust command and control over nuclear and supporting government operations. The second layer provides the survivable, secure, and enduring architecture known as the “thin-line.”

Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear Matters, Nuclear Matters Handbook 2020 [Revised], https://www.acq.osd.mil/ncbdp/nm/NMHB2020rev/chapters/chapter2.html.