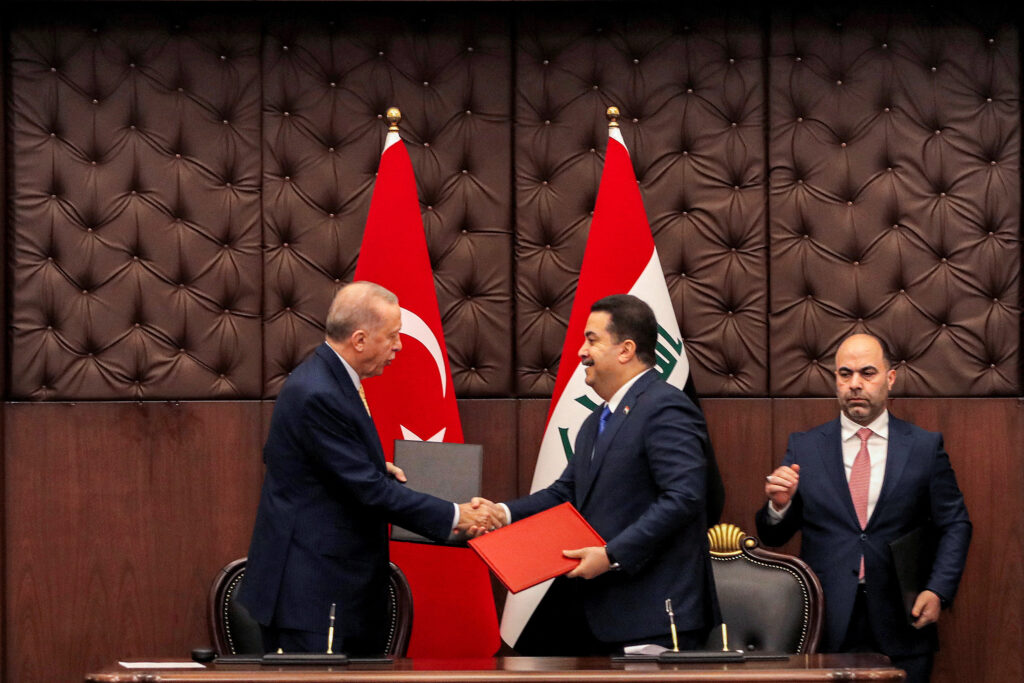

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Iraq in late April, his first such visit in over a decade and his first as president.

The visit by Erdoğan and a large delegation of ministers and other officials yielded a raft of new bilateral agreements, positive optics after several years of tense relations, and new opportunities for strategic cooperation in critical fields such as energy, trade, and security.

The visit marked a major pivot in the Iraq-Turkey relationship—and how Ankara and Baghdad portray it. Despite parts of the visit that may come off as performative, the meeting did set the stage for improved regional stability and prosperity, with knock-on effects for the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Iraq-Turkey relations have been fraught for the past decade, driven in part by an acrimonious international legal battle over the export of KRG oil through a pipeline to Turkey without Baghdad’s permission. The two have bickered over Turkish military operations against Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants on Iraqi soil, with Ankara charging Iraq with tolerating presence of the Foreign Terrorist Organization-designated group and Baghdad charging the Turks with violating Iraq’s sovereignty. Disputes over water flows from the Euphrates and Tigris remain thorny too.

Yet with the broader Middle East roiling due to the war in Gaza and increasingly open conflict between Israel and Iran, leaders in Turkey and Iraq seem to have realized the need to protect their interests and shore up stability through regional cooperation. With a year of careful diplomatic groundwork laid since the May 2023 Turkish elections, the two sides prepared an agenda with an ambitious set of economic, security, and diplomatic goals. Chief among these have been Baghdad’s decision to ban the PKK, a commitment to repair the portion of the Iraq-Turkey oil pipeline that doesn’t run through the KRG, and a multilateral agreement (also signed by ministers from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates) to cooperate on a trade corridor from the Gulf to Europe with a new network of roads and railways through Iraq and Turkey.

The United States and Iran, although not openly discussed, played a role in motivating the visit. Baghdad remains dependent on Washington for counterterrorism assistance and financial assistance, despite calling publicly for US troops to leave—and would like to reduce that dependence through stronger security and development cooperation with Turkey and the Gulf. Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ Al-Sudani has to cope delicately with Iranian influence over Iraqi politics and security as he tries to balance or reduce it, and better ties with Turkey are another dimension of that strategy. In a region subject to cutthroat competition among great powers (and also mid-sized ones), local cooperation strengthens defensive leverage.

As one observer in Erbil noted during the visit, the symbolic purpose of the visit for Iraq was to show that Baghdad has productive relations with its neighbors to the north and south, not just with the dominant one to the east. “Caliph Abu Jaafar al-Mansour built four gates for the city, the main one facing Khorasan . . . but the gate of Baghdad was not only open to Iran and Khorasan,” the commentator wrote. He relayed remarks from several Iraqi officials that “Erdogan’s arrival signifies a new stage for them. This shows that not only the Khorasan gate of Baghdad is open.”

Generally low trust in US plans for the region provides Turkey and Iraq—both US allies—additional incentives to hedge through local cooperation. Most Iraqis (and Turks) doubt US commitment to stability, sovereignty, and democracy in the region. Regional observers are skeptical whether the United States has militarily deterred Iran in Iraq or Syria or whether it is even possible for Washington to do so—and such observers aren’t that anxious to see it try. Tellingly, the United States has backed a major development and transit project, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), that bypasses both Turkey and Iraq.

Countering IMEC seems to have given new impetus to efforts at a bilateral reset between Baghdad and Ankara. The Development Road project (launched by Iraq in 2023) centers on a 1,200-kilometer highway and rail system linking al-Faw Grand Port in Iraq’s Basra province to international markets. Now, with the agreements solidified last week, that route is set to run through Turkey, with investment and participation from both Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. The project is expected to not only generate a projected four billion dollars in annual income (on a seventeen-billion-dollar initial investment) but also create over one hundred thousand jobs and further integrate Iraq into regional and global economic networks.

Beyond the quadrilateral signing of the agreement to cooperate on the Development Road project, Erdoğan’s visit yielded a Turkey-Iraq strategic framework with nearly thirty separate agreements. Senior officials from both the Iraqi and Turkish ministries of trade, energy, agriculture, transportation, health, defense, and foreign affairs participated and agreed to permanent joint committees to reenergize the 2008 High Level Strategic Cooperation Council mechanism. From Ankara’s perspective, cooperation and legal authorization for its anti-PKK operations is the most pressing area to see concrete developments. For Iraq, a collaborative and mutually profitable approach on water and oil are high priorities. Of course, fulfillment—not just the announcement—of these cooperative agreements will be the parameter for success, but to hold such a high-level, detailed, and ambitious foundational meeting was a good start.

The visit was portrayed positively, albeit with different emphases, in the Iraqi and Turkish national press. Turkish reporting noted Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan’s patient diplomacy and strategic design, highlighted the potential mutual economic gains, and outlined potential benefits of the Development Road—such as its role in possibly eroding de facto PKK control of large areas in northern Iraq. Iraqi media focused on the need to overcome longstanding problems and on the ample room for growth and improvement in ties. Kurdish coverage quoted officials and experts praising Turkish engagement in Iraq and underscoring the need for Ankara to sustain close ties with Erbil, as well as Baghdad, to prevent the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s exclusion from the benefits of closer national ties.

This apparent new chapter in bilateral relations has limits and brings risks. One limit is the central Iraqi government’s relatively limited reach with regards to the PKK. It has scarce military or intelligence resources in the remote border areas where the PKK operates and scant motive to commit them. There is some possibility that Baghdad is dangling potential counter-PKK support to co-opt Ankara into reducing support to the KRG. Therein lies a strategic risk for Ankara to guard against: Close Ankara-Erbil ties have had tremendous economic and security benefits for both. Another limit is Iran’s continuing influence over Baghdad and suspicion of Turkish influence there, which its agents and proxies will certainly seek to minimize.

The Development Road adds a dynamic new economic element to the bilateral equation, though, making it likely that the promise of more neighborly ties is less theatrical, and more substantive, than past expressions of intent. A practical and institutionalized strategic framework, coupled with an increasingly turbulent region and a newly compelling economic project with Gulf support, means that the current pivot may be both sincere and strategically significant. Handled deftly, it may produce the most stable Iraq—and a real community of interest between the two neighbors—the world has seen since Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

Colonel (retired) Rich Outzen is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Turkey program. He served thirty years in the US Army—with tours in Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkey, Israel, and Germany—and served in senior policy positions at the State Department and Department of Defense.

Further reading

Fri, Feb 2, 2024

Where Erdogan loses balance

The Big Story By

Turkey’s president has become a central player in world affairs by balancing competing interests. But in the conflict roiling the Middle East, he risks being left out of the game.

Tue, Jan 9, 2024

Can Turkey help resolve the Israel-Hamas war?

TURKEYSource By Matthew Bryza

Turkey once offered to secure a role in de-escalating the conflict and in serving as a guarantor of a future ceasefire. Months later, can Turkey still play that role?

Fri, Jul 21, 2023

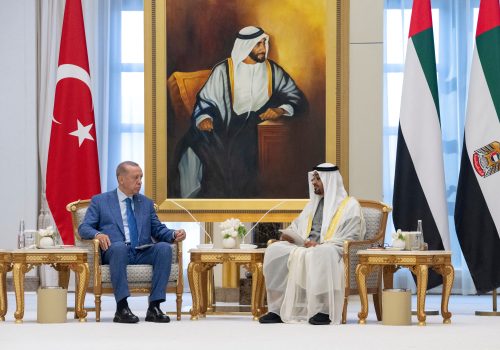

What’s behind growing ties between Turkey and the Gulf states

TURKEYSource By

Erdoğan's tour of the Gulf opens a new chapter in Turkey's political and economic relations with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

Image: Iraq's Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani and Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan exchange signed agreements during their meeting in Baghdad, Iraq April 22, 2024. AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/Pool via REUTERS