The pardoning and release of a convicted Iranian war criminal is a crime

The recent decision by the Swedish government to pardon Hamid Noury, a convicted war criminal involved in mass executions, and to return him to Iran in a prisoner exchange on June 15, sets a dangerous precedent with far-reaching consequences. This exchange, involving the release of Swedish diplomat Johan Floderus and dual national Saeed Azizi, highlights the Islamic Republic of Iran’s use of “hostage diplomacy” to achieve its aims.

This exchange has been an agonizing personal blow. Since 1981, when my brother Bijan Bazargan, a college student, was arrested, my family fought tirelessly for his release, clinging to the belief that supporting a political group or distributing pamphlets should not merit a ten-year sentence. In the summer of 1988, my brother was secretly executed, and his body was never returned—making him one of the countless forcibly disappeared.

After years of activism, conferences, and gatherings to expose the horrors of the 1988 massacre of political prisoners, Noury’s arrest felt like the hard work of those decades had finally paid off. It was the first time a perpetrator had been held accountable, and this opened a small window of hope. But when the Swedish government pardoned Noury, I was overwhelmed by a sense of betrayal and fury.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

Although this decision saved two innocent people from Iranian jails, it was a mockery of justice. It emboldened a terrorist regime that uses hostage diplomacy to achieve its goals. Noury returned to a hero’s welcome in Iran, with flowers and a red carpet, surrounded by dozens of reporters. He mocked the families of the victims on television, laughing at our pain and the entire justice system. This prisoner swap deeply undermines trust in the international justice system, promotes the desire for revenge and vengeance, and breeds chaos and despair.

While Noury committed war crimes and murder, Floderus had merely traveled to Iran to visit friends and sightsee, and Azizi had gone to Iran to take care of his property’s water leakage. The gross imbalance in this exchange is alarming. How can a state justify swapping individuals detained under dubious circumstances for a man convicted of heinous crimes against humanity?

The case against Hamid Noury

Noury was convicted of war crimes and murder for his role in the 1988 massacre of political prisoners; he was assistant to the deputy prosecutor of Gohardasht prison in Karaj near Tehran. This event saw thousands extrajudicially executed on the orders of founder Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Khomeini’s fatwa ordered the executors to make decisions “based on prison records and [the] simple question, whether prisoners believed in the Islamic regime or not.” He also instructed them “not to hesitate or show any doubt or be concerned with details…and be most ferocious against infidels,” a reference to political prisoners who did not want to repent and accept the regime’s version of religion and ideology.

On November 9, 2019, during his visit to Sweden, Noury was arrested at Stockholm Airport under the principle of universal jurisdiction. His trial was significant because it was one of the first times someone was held accountable for the 1988 massacre.

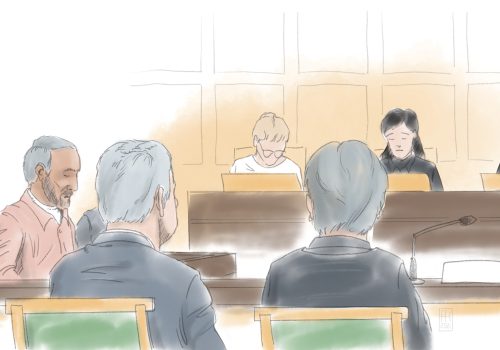

Survivors and victims’ families endured an arduous legal battle, participating in ninety-three district court sessions and twenty-two appellate court sessions, while facing constant lies and ridicule from Noury. Throughout the trial, the former official frequently turned his back on the plaintiffs, mocked them, and used derogatory language to demean them. His family exacerbated the situation by filming the plaintiffs and labeling them terrorists who deserved to die.

In 2022, Noury was sentenced to life imprisonment for his role in the 1988 massacre. At the time, his trial and subsequent conviction in Sweden were celebrated as significant steps for international justice.

However, his return to Iran in a political exchange undermines these achievements, and potentially emboldens other rogue regimes globally.

Injustice is served

On May 29, the Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson proposed a draft law to the Legislative Council to expedite the transfer of prison sentences to and from Sweden, aiming to increase the number of convicts serving sentences in their home countries. Plaintiffs were alarmed by this development and began strategizing ways to oppose the amendment, which is set to take effect on July 1, 2025. While preparing for that fight, they were blindsided by the sudden pardon and release of Noury, who was sent back to Iran.

Sweden’s decision to use an existing law to pardon Noury and send him back to Iran raises several legal and ethical questions. The law allows the government to pardon or mitigate a criminal penalty for “exceptional reasons.” However, the legality of applying this law to someone convicted of war crimes is highly dubious. International norms and laws suggest that individuals accused of war crimes should not be eligible for pardons. War crimes are generally considered so egregious that they fall outside the scope of typical criminal acts that might be mitigated or pardoned under domestic laws.

Additionally, as part of his conviction, the Swedish court had ordered Noury to pay reparations to the plaintiffs. Although the amount was symbolic, it represented a debt owed to the victims—some of whom are Swedish citizens. The government should have considered this obligation before deciding to release Noury. Ignoring this debt disregards the justice system’s recognition of the harm caused to the victims and their families.

The public reaction to Noury’s release has been overwhelmingly negative. His release has also created profound disappointment among Iranians and disbelief in international norms and human rights laws. It was already challenging to discuss justice, accountability, and transitional justice, given the Islamic Republic’s forty-six-year history of committing atrocities. These include the chain murders of intellectuals and writers inside Iran during the 1990s, the crushing of the 2009 post-election protests known as the Green Movement, the killing of a reported 1,500 protesters during November 2019 (known as “Bloody November”), the killing, blinding, arresting, and torturing of protesters during the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, and continued transnational repression. The Swedish government’s decision adds to the demands of victims’ family members for retribution and revenge.

This decision—which undermines the principles of accountability and justice the international community has strived to uphold—sends a dangerous message that even those convicted of the most grave human rights abuses can evade justice through political maneuvering.

It also potentially encourages the hostage-taking policies of Russia, Venezuela, and terrorist organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah, and leaves behind numerous foreigners and dual citizens, including at least three Swedish nationals. Hostage diplomacy gives brutal regimes political leverage, allowing them to extract concessions, sanctions relief, or the release of their own imprisoned nationals. Each successful negotiation sets a precedent, suggesting that detaining foreigners can lead to diplomatic engagement and tangible benefits, thereby encouraging the continuation and expansion of these tactics.

This release has left numerous foreigners and dual citizens in imminent danger of execution in Iran—including Swedish national Ahmadreza Jalali, whose death sentence has already been issued. Excluding them from these negotiations sent a clear message that they are not as important as a European diplomat. This decision underscores the need for a more comprehensive approach to international hostage negotiations that value all human lives equally.

Noury’s pardon despite his war crimes conviction risks further emboldening the Islamic Republic. It undermines the independent judiciary system, signaling to other regimes that such serious crimes might not face significant consequences. The Swedish government must be transparent and explain why it made such a decision.

The fight for justice is far from over, and the families of the victims of the Islamic Republic’s atrocities, along with human rights advocates worldwide, continue to call for accountability and the end of impunity for crimes against humanity. The global community must stand firm in this endeavor, ensuring that justice prevails and that the security and dignity of all individuals are upheld.

Lawdan Bazargan is a former political prisoner, human rights activist, and family member of one of the victims of the 1988 prison massacre in Iran. As a member of Victims’ Families for Transitional Justice, she advocates for justice and explores the profound grief of those seeking accountability for the atrocities committed.

Further reading

Thu, Aug 4, 2022

My brother was executed during the 1988 massacre. The Hamid Noury trial verdict is a victory for truth and justice.

IranSource By

Only the truth can heal Iran and the Iranian people’s collective pain and protect future generations from the danger of such crimes.

Thu, Jun 27, 2024

Sweden released an Iranian war criminal. Here’s how activists and rights defenders reacted.

IranSource By

World powers will continue negotiating with the Islamic Republic and make shortsighted concessions that will endanger not only the future of Iran but also global security. However, the fight for the liberation of Iran is not over—at least for Iranians.

Thu, Nov 10, 2022

The Hamid Noury conviction in Stockholm—a win for People’s Tribunals?

IranSource By

The former Iranian official’s conviction sends a powerful message: although the mills of justice may grind slowly, nobody can remain beyond the reach of justice forever.

Image: An unidentified man talks to Khadijeh Ramezani (C), mother of the former staff member of the Iranian judiciary, Hamid Nouri, as she arrives to attend a protest gathering in front of the Sweden Embassy in northern Tehran on July 19, 2022. Nouri was sentenced to life imprisonment by a Swedish court on July 14. (Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto)