In anticipation of growing demand for zero-emission transportation, China has become the world’s largest exporter of electric vehicles (EVs). China’s battery electric vehicle (BEV) industry is at overcapacity, producing an excess of 5 to 10 million vehicles annually beyond domestic demand, forcing China to find new markets to fuel continued growth.

Brazil offers a useful case study of China’s strategy—and whether it’s sustainable.

STAY CONNECTED

Sign up for PowerPlay, the Atlantic Council’s bimonthly newsletter keeping you up to date on all facets of the energy transition.

Over the course of 2023, the value of Chinese BEV exports to Brazil surged eighteen-fold as automakers like BYD expanded their presence in the country. Chinese BEVs accounted for 92 percent of Brazil’s total BEV imports in this period.

This trend has continued durably thus far. As of April 2024, Brazil has surpassed Belgium as the top export market for China’s EVs.

Those aren’t the only numbers pointing to Brazil’s growing prominence as a market for Chinese BEVs, which constitute 88 percent of China’s total exports of electric vehicles, a category which includes both battery and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs).

In fact, Brazil imported $735 million worth of Chinese BEVs in 2023, nearly three times the value of Mexico’s imports of these Chinese vehicles. Despite increasing attention on Mexico as a destination for exports of Chinese BEVs, 2023 marked the second straight year that Brazil has ranked as Latin America’s largest importer of Chinese BEVs.

Furthermore, growth in Chinese exports of BEVs to Brazil far exceeded the overall rate of increase in exports across China’s “new three” industries—electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and solar photovoltaic cells—that are critical pillars of China’s export-driven manufacturing plans. In 2023, China’s worldwide exports of these three industries increased by 30 percent—a significant jump amid sluggish global GDP growth overall, suggesting limited ability for markets to absorb this export growth.

Whether Brazil can continue to absorb China’s overproduction of BEVs, similarly, is increasingly in doubt.

Strong domestic sales, slacking foreign competition

In recent years, EV sales in China have been robust, with BEVs—which are almost entirely produced domestically—accounting for 25 percent of total car sales in 2023. It is worth noting that this includes foreign firms, however, such as Tesla and Volkswagen.

China’s manufacturing of BEVs has outpaced domestic demand. While this might have resulted in millions of cars sitting unsold in Chinese lots, the overproduction has coincided with Western automakers such as General Motors, Ford, and Volkswagen tempering their EV ambitions amid weakening demand growth in their core markets.

This confluence of trends created an opportunity for Chinese BEV makers to boost sales abroad, as demonstrated by the 70 percent jump in BEV exports during 2023. Chinese BEV firms, and BYD in particular, are making a concerted effort to expand outside of mainland China, offering products that outcompete peers on price, and sometimes compete strongly with internal combustion engine vehicles.

China’s growth ambitions cause concern

Rather than incentivize consumption, China is doubling down on its investment-driven growth model with an upcoming manufacturing stimulus program. Investment, expressed in World Bank data as gross capital formation, already represents 40 percent of China’s GDP, far above the global average of 25 percent and exceeding the emerging market average of 30 to 34 percent, illustrating China’s reliance on sectors like manufacturing to fuel growth.

China’s decision to expand its export-driven manufacturing sector is causing handwringing in target markets. The Brazilian government has opened a number of probes into China’s alleged “dumping” of goods. The European Union has also opened investigations into potential “non-market practices and policies” adopted by China.

China’s exports of its record surplus of manufactured goods beyond current levels will depend on other countries’ willingness to let China take market share from domestic industry. In an increasingly protectionist era, that seems far-fetched.

Will Brazil absorb China’s manufacturing surplus?

The surge in imports of BEVs from China has been rapid, offering little time to react. However, for Brazil, the stakes for its industrial competitiveness are high, and its tolerance for China’s encroachment on its automotive industry may be limited.

For one, automobiles are a critical cog in Brazilian industry. As of 2020, 89 percent of vehicles sold in the country were domestically produced, although this may have decreased slightly amid a surge of Chinese BEV imports. The car sector accounts for about 20 percent of industrial GDP, an area of critical importance to Brazil, where value-added manufacturing’s share of GDP has declined from 26 percent in 1993 to 11 percent in 2022.

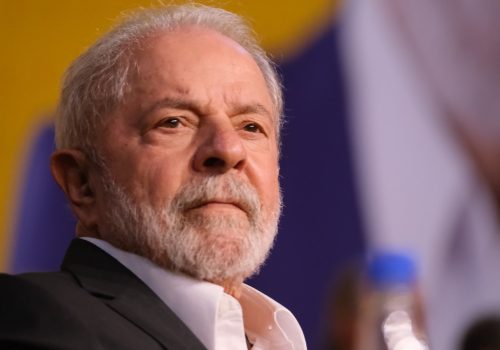

Second, Brazil does not want to deepen its reliance on imports of high-tech and value-added products. In 2021, Brazil’s imports of capital, consumer, and intermediate goods accounted for 93 percent of total goods imports, a symptom of the country’s increasing trade specialization in the export of raw materials, which represented 55.7 percent of Brazil’s exports of goods. The government has expressed its discontent with this status quo, seeking to avoid trade arrangements that “condemn our county to be an eternal exporter of raw materials,” in the words of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Furthermore, Brazil has made supporting the domestic auto sector a priority. In May 2023, the Lula administration unveiled a series of measures to promote domestic auto manufacturing via credit lines, tax breaks, and incentives for the use of domestic content.

A continued rise in cheap Chinese EV imports would not align with Lula’s top-down push for re-industrialization, designed to foster formal high-wage employment, innovation, and economic diversification. In fact, his administration has announced new tariffs on electric vehicles, which will ramp up to a 35 percent import tax by 2026.

As such, China will likely need to find more willing buyers of its surplus EVs. Although it is difficult to forecast where the next surge in imports will take place, South and Southeast Asian markets such as India, Indonesia, and Thailand could begin to exhibit stronger uptake, as could markets in Latin America such as Colombia and Mexico.

William Tobin is an assistant director at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

MEET THE AUTHOR

RELATED CONTENT

OUR WORK

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.