The case for the United States and China working together in space

In the fall of 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent then Senator Lyndon B Johnson to the United Nations (UN) with the proposal that “the exploration of outer space be undertaken for peaceful purposes, as an enterprise of international cooperation among all member nations.” The resolution reflected a growing aspiration that nations would join together in exploring the cosmos and in doing so find a common purpose.

The vision was amplified by Johnson when he became president. In a letter to the Senate in 1967, he emphasized that cooperation in space would provide a basis by which to avoid confrontational national tendencies, thereby leading to substantial contributions toward peace. The historic US Apollo and Soviet Union Soyuz (Apollo-Soyuz) docking in July 1975 was heralded as a first step toward meaningful space cooperation between otherwise adversarial nations. The image of astronauts and cosmonauts welcoming each other across their open spacecraft hatchways sparked an optimism and a sense of unity that inspired the world community. NASA astronaut Tom Stafford said that opening the hatch in space opened a “new era” back on Earth.

The current state of space diplomacy

Today, the International Space Station is a testament to multinational cooperation, persisting despite seismic geopolitical shifts. The partnership between the United States, Europe, Canada, Japan, and Russia has required a myriad of joint engineering projects and mutual reliance on resources despite monumental earthly tensions—a striking step forward in space diplomacy.

In recent years, however, hostility between the United States on one hand and Russia and China on the other has overshadowed the core tenets of space cooperation. The realization that space is not only an arena for scientific exploration and economic competition, but of future military conflict, has come to the fore. Although the United States and forty-two other nations have recently agreed to a set of principles for the peaceful exploration of space, known as the Artemis Accords, there exists no such agreement with other key space-faring nations, most notably China and Russia.

Parallel lunar ambitions

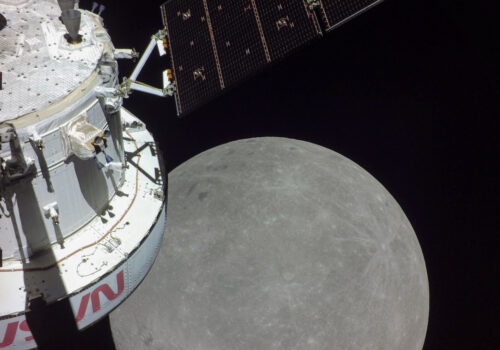

The United States and its allies are developing a major space program to return to the moon and establish a permanent presence with a lunar base and an orbiting lunar space station. The project has ignited public excitement and forged new agreements between the United States and partner nations. At the same time, China is leading a very similar project called the International Lunar Research Station to establish a permanent lunar presence, working with Russia and several other countries, including Belarus, Egypt, Nicaragua, and South Africa.

Two groups of nations separately working on the same goal, establishing separate lunar bases with no cooperation between them is a disappointing setback from earlier achievements. One might ask: What happened to the spirit that drove the handshake on Apollo-Soyuz?

There are of course challenges and barriers to sparking and sustaining cooperation. The growing conflicts on Earth and the threats posed by anti-satellite weapons provide arguments against initiating a dialogue. However, similar dynamics were present in the past, when leaders decided to work together to embrace the common objectives of exploring the cosmos and harvesting space for the betterment of life on Earth. Despite major tensions and conflicts, the two sides gained a measure of mutual understanding and respect for each other’s humanity through the efforts of scientists, engineers, and astronauts, as they joined in a common purpose.

Starting points for US-China space cooperation

The logical question is: Given substantial concerns regarding military hostility in space, where should the United States and China start? How can they find common ground in an environment of such intense mistrust?

Washington and Beijing can begin with a principle that has already been agreed upon and that touches a core human value. The UN Rescue and Return of Astronauts Agreement came into effect in 1968. It commits nations to come to the assistance of astronauts in distress, no matter what country they launched from. It was a noble step forward, and a theme largely taken from the finest of maritime traditions. The agreement, however, is hollow without plans, procedures, and systems in place to enable meaningful action. Spaceships and space suits are complex and unique, and without forethought and the right equipment it is highly unlikely that astronauts from separate nations could possibly provide any meaningful aid. For instance, how would a Chinese astronaut connect and supply the right pressure to provide oxygen to an American astronaut in distress without first having the right connecting gear and knowing the pressure settings? How can countries make their ships compatible to dock if medical support is needed? What would be the communication protocols to use when determining whether assistance is necessary?

A bilateral working group between NASA and China’s National Space Administration (CNSA) should be established to prepare for joint rescue operations. This interaction would lead to improved communication between the respective space communities. The collaboration would also establish readiness for potential rescue missions, which would have profound benefits in the event that an astronaut rescue was needed.

Once the rescue working group is formed, further bilateral agreements should be pursued. These could include mutual use of lunar communication and navigation services, as well as agreements on providing consumables, power, habitats, and transport.

What steps does the United States need to take? The United States should repeal the Wolf Amendment, which was put in place in 2011 due to concerns about space technology transfer to China. The establishment of this barrier has not slowed China’s space technology development. Instead, it has only hindered useful interchange between NASA and the CNSA.

And China? Beijing should foster more open communication with the United States regarding norms of behavior in space exploration and the preservation of the space environment. It should take a leading role in space sustainability, including being transparent about its plans to remedy issues with the Long March 6A rocket that broke apart earlier this month and left significant space debris. China should also initiate discussions to join moratoria on destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing, which it has so far opposed.

Eisenhower and Johnson advocated for cooperation to prevent misunderstandings and mistrust from growing into armed conflict in space. They saw the need to take firm steps to avoid such a tragic result. To that end, the United States and China must now take swift steps to initiate space cooperation and lead a more unified world into the final frontier.

Dan Hart is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoTech Center.

Further reading

Thu, Feb 15, 2024

Experts react: What to know about Russia’s apparent plans for a space-based nuclear weapon

Experts react By

Reports that Russia is developing a space-based nuclear anti-satellite weapon have raised national security concerns in Washington.

Fri, Apr 12, 2024

Why the White House wants to know what time it is on the Moon

New Atlanticist By Lloyd Whitman

Developing international standards for keeping time on the Moon could be critical for the success of planned crewed lunar missions.

Fri, Oct 13, 2023

Mobilizing public science priorities through the American commercial space industry

GeoTech Cues By Ellie Creasey, Tiffany Vora

The next ten years stand to be transformative for improving life on our planet while simultaneously achieving a sustainable and thriving human presence beyond Earth.

Image: Handout photo dated December 5 2022 the Moon is seen from cameras onboard NASA s Orion spacecraft during the 20th day of the Artemis I mission These images were taken after Orion executed the Return Trajectory Correction 3 burn to prepare it for the Return Powered Flyby maneuver bringing it on its second close approach to the lunar surface and continuing the journey back to Earth. Photo by NASA