The Atlantic imperative

A decade ago, to mark the Atlantic Council’s fiftieth anniversary, the scholar N. W. Collins embarked on an ambitious project to trace the Council’s origins, illuminate the vision of its founders, and chart its intellectual and institutional evolution over the decades. Drawing on interviews with Council leaders and national policymakers along with archival research from across the country, Collins presented her findings in the essay below.

The founding moment

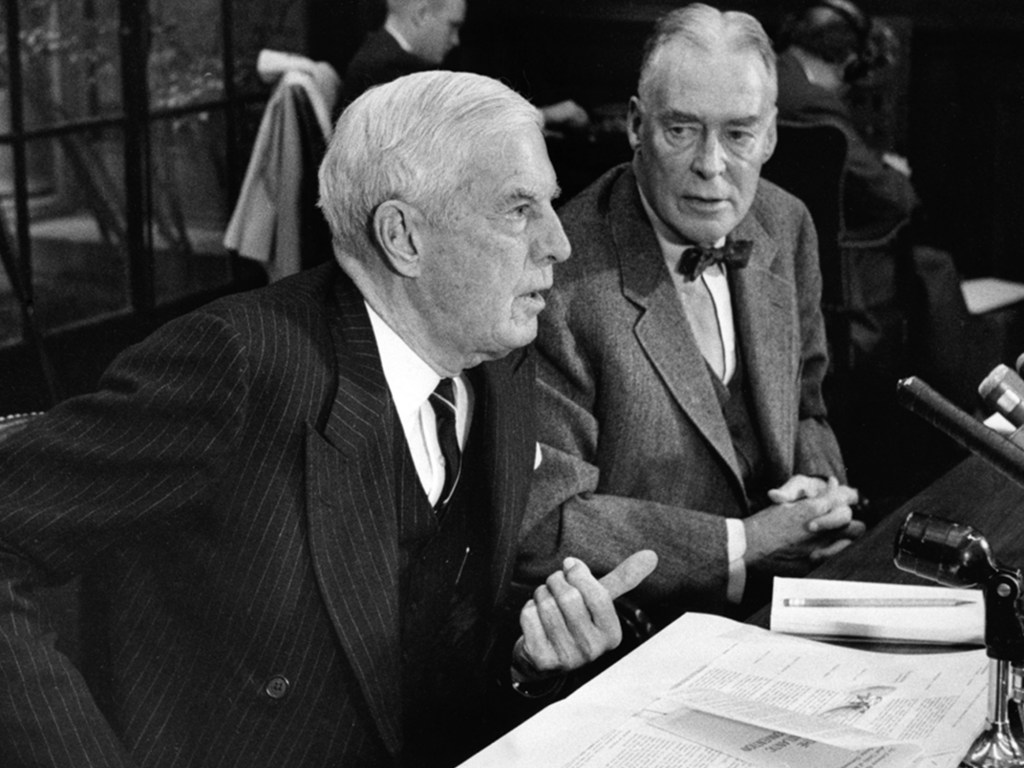

Dean Rusk demanded solutions. Sitting in his conference room on the seventh floor of the State Department, on July 24, 1961, President Kennedy’s new secretary of state told a group of America’s leading Atlanticists—among them Dean Acheson, Christian Herter, and Henry Cabot Lodge—that he wouldn’t work with them until they developed a unified voice.

It was one of many difficulties that he was having that summer. Rusk hadn’t wanted this job, and few had expected Kennedy to select him. But six months earlier, he had assumed office with high hopes and much fanfare, including an appearance on the cover of Time magazine. He had said then, “It’s our turn now, and we will do better.”

The first few months had not lived up to that promise, and the problems were now mounting: the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, in April, had been followed by the Vienna summit, in June, which had been marked by Nikita Khrushchev’s belligerent stance toward Kennedy—notably his threat that US policies regarding Berlin could result in war. Kennedy had come away deeply concerned that Khrushchev would test him that year.

That afternoon, Rusk wanted to address one concern in particular: the cacophony of Atlanticist voices at a time when America might be facing a crisis in Berlin. If he could finesse it, he would convert a brilliant but unruly bunch into a constructive entity that could serve the Kennedy administration. This was not his usual milieu, but his decade as president of the Rockefeller Foundation had given him a familiarity with the intellectual and policy debates of the transatlantic community, and his experiences in the 1930s as a student in Berlin, when the Reichstag burned and Hitler seized power, had convinced him of the centrality of Europe to US national-security interests. While Rusk frequently expressed frustration with his European counterparts—especially when he worked on the State Department’s efforts to lift the Berlin blockade in 1948, and later, during his years as secretary of state when he had described Europe as “comfortable and fat, somewhat lazy about its international responsibilities”—he was nonetheless determined to push for greater allied engagement. In his autobiography, As I Saw It, he described his efforts as heckling and cajoling friends on both sides of the ocean, trying to persuade Europeans to build up their defense budgets and Americans to come together to strengthen Continental forces: “In general, we wanted Europe to do more rather than less on the world scene.”

Rusk called on the fifteen Atlanticists assembled in his conference room that day, who had affiliations with more than two dozen transatlantic groups, to come up with a remedy to the problem of transatlantic policy structures, which he characterized as overlapping and diffuse to the point of being counterproductive. Rusk went around the table, calling for comments from those present—most prominently, former Secretary of State Christian Herter and former US Ambassador to the United Nations Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. Deciding that he didn’t like any of their answers, he weighed in with his own. He wanted them to consolidate the existing Atlantic organizations into a single entity and asked them to settle the matter during the next four to six weeks.

Lodge, rebounding from a tough campaign as Richard Nixon’s vice presidential candidate, in 1960, sat there silently. He made no comment on the idea of the merger, and instead responded by extolling the virtues of a new organization, the Atlantic Institute, which had recently been founded in Paris and which he would soon lead.

William Foster, an expert on arms control and nuclear proliferation, described himself to the group as very likely belonging to more of the Atlantic organizations than anyone else present, and said that he would keep an open mind regarding Rusk’s suggestion. He concurred with Lodge that the new Atlantic Institute would be the ideal vehicle to absorb the wide range of existing organizations. Robert Murphy, who had served as US ambassador to Japan and to Belgium, expressed his concern that the idea of merging the disparate groups into one Atlantic institution might actually constrain the transatlantic community, resulting in a body with a narrow geographic range rather than one that promoted the internationalist mindset he favored.

Christian Herter, secretary of state under President Eisenhower, and Rusk’s immediate predecessor, did not respond directly to Rusk’s pitch, but stated that if such an association came into existence, he would favor a new one that would work toward the broadest Atlantic interests and would not be limited to military needs on the Continent or to issues within certain geographic boundaries. Herter argued that an Atlantic institution should devote itself to problem-solving on a wide range of political, economic, and social issues relevant to the entire international community, approaching them from a core of consistent Atlantic values. He wanted to put into global practice the values in which they all believed.

That dialogue might have reached a dead end were it not for the crisis that was building at that moment, which would culminate with the construction of the Berlin Wall in August, and then with the US-Soviet tank standoff at Checkpoint Charlie in October—events that led many experts to speculate that the Cold War would soon turn hot, or even nuclear. Owing to these developments, among others, Herter understood Rusk’s insistence upon consolidation.

By year’s end, Herter had signed on as the chairman of a new organization, the Atlantic Council, and Mary Lord signed on as a founder and the sole signatory of the by-laws and the certificate of incorporation, in September and December 1961, respectively. Dean Acheson and Will Clayton joined as vice chairs; Amory Houghton Jr., Thomas Watson Jr., and Elmo Roper were appointed to the board of directors; and Theodore Achilles was named director, responsible for running the day-to-day affairs.

In the late autumn of 1961, the group set up offices in the eleven-story Grange Building, one block from the White House, which had been dedicated by President Eisenhower just the year before. At its first executive committee meeting in December of 1961, the Council approved a plan to serve as the US office for two European counterpart organizations—the Atlantic Institute and the Atlantic Treaty Association, both headquartered in Paris, to ensure a unified effort. In advance of the first full board meeting, in March 1962, the Council recruited the three living former US presidents—Hoover, Truman, and Eisenhower—to be honorary chairs. This had been a priority for Herter, who sought to demonstrate both the Council’s nonpartisan nature and its high-profile cause. The group’s sights were set on no less than the formulation of new actionable policies for the free nations of the world—from creating educational programs in developing nations to influencing Sino-Soviet relations—while increasing the appreciation of international democratic activities in the eyes of all Americans.

A standing ovation

Christian Herter was tireless in establishing the Council’s position as a policy organization for transatlantic security and economic cooperation. He led board delegations to NATO and European Economic Community meetings in Europe to boost interest in expanding Atlantic institutions, engaging prominent US citizens to become active participants including James B. Conant, former president of Harvard University; John J. McCloy, president of the Council on Foreign Relations and previously the US high commissioner for Germany; and Matthew B. Ridgway, formerly the Supreme Allied Commander Europe and the Army’s chief of staff. In the first year, Herter’s efforts led directly to the Declaration of Paris, signed in January 1962 at the Atlantic Convention of NATO nations, which called for the establishment of new transatlantic economic and legal institutions to create a common trade marketplace.

At the start of his second year as board chairman, however, Herter received the call to return to government service, this time as President Kennedy’s trade representative. Herter shared the news with Acheson, informing him that it was likely he would step down from the chairmanship that winter. Acheson began a quiet search to fill this looming leadership vacuum, to ensure a seamless transition for the nascent organization.

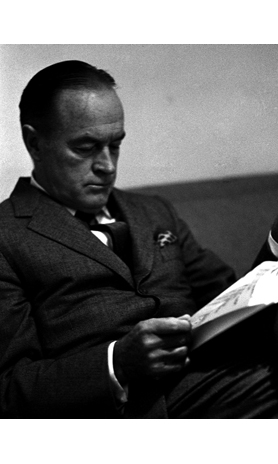

Within weeks, Dean Acheson had identified one person as being more qualified than all others: General Lauris Norstad. A military hero under Eisenhower and then Kennedy, Norstad was nearing the completion of thirty-eight years of military service, with a retirement date set for December 31, 1962. Much decorated for his World War II combat in Algeria and Italy, and holding multiple European and NATO command positions in the 1940s and 1950s, Norstad was completing a final command as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). A congressional resolution passed that October best captured Norstad’s public profile at that time, recognizing his vital role in the arena of transatlantic security and crediting his decade-plus leadership in Europe as essential to developing Western forces of strategic deterrence.

As a naturalized American citizen, whose family roots were in Norway, Norstad personified Atlanticism. Furthermore, he had a striking presence. At the age of forty-one, Life magazine had selected him to be on its cover, describing Norstad as the “Air Force’s Thinker,” leading a new generation of pilots. News reports frequently focused on his central-casting good looks and lanky figure, first in Air Force blues and then, as he started civilian life, nattily turned out in gray three-piece suits.

Now at the age of fifty-five, Norstad did not seem to be slowing down; on the contrary, he was ramping up for the next phase of his life. In early January 1963, at a medal ceremony hosted by President Kennedy at the White House, Norstad shared some advice that he had received from an old doctor friend on how to live one’s life: Run, don’t walk. He had taken this counsel to heart, he said, choosing not to retire, as many were expecting, but rather to begin a second career, in corporate life, as president of Owens Corning’s international division.

It was up to Acheson to convince him that the next chapter of his life would also ideally include the chairmanship of the Council, succeeding Herter. Acheson had already arranged the Council’s first gala at the Mayflower Hotel—hosted by the three living past US presidents—to honor Norstad for his NATO leadership. As the date approached and Herter’s return to government was publicly announced, Acheson sought to persuade Norstad to accept the Council role and to mark this leadership transition at the Mayflower event.

At the last moment, Norstad agreed, and on January 14, 1963 five hundred people—including President Kennedy—gathered in the ballroom to toast Norstad and, as it turned out, his new role at the Council’s helm. A remarkable crowd gave him a standing ovation that evening, including Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, Paul Nitze, Allen Dulles, Admiral John McCain, General William Draper Jr., Service Chiefs Cyrus Vance (Army), Fred Korth (Navy), and Eugene Martin Zuckert (Air Force), and ambassadors to the United States from all the NATO countries.

Moreover, the Mayflower dinner was memorable for an unexpected policy address. Acheson had envisioned the event as showcasing Atlantic unity for common security, in which policy disagreements would be largely set aside for the night. Norstad, however, used his time at the podium to call pointedly for atomic weapons that were wholly committed to the Alliance and to talk about changes in control over the supply and use of these weapons.

Norstad advocated an executive authority made up of the three nations possessing nuclear capability—the United States, Britain, and France—which would then decide on the emergency use of such weapons by majority agreement. This new decision-making structure, he argued, would recognize the role of European nuclear power, acknowledge that the Continent was no longer the collection of war-shattered nations it had been in the 1940s, and give European leaders a larger role in determining the use of weapons in their territories. This would not only create a more balanced security partnership, Norstad argued, but would also avoid the problem of unworkable military safeguards or coordination—notably, the problem of having fifteen fingers (all of the NATO members) on the atomic trigger.

That provocative speech kicked off a multi-year debate inside the Council. Under Norstad’s chairmanship, the Council worked to define the specific goals and practices of its transatlantic mission. While nearly all the members agreed with the idea that Atlantic unity could provide a basis for promoting democracy, law, and trade, there was little consensus in the early days on the Council’s scope or on the concrete steps necessary to carry out various Atlantic ideas.

Mary Lord, a co-founder and board member of the Council, emphasized a one-world approach to Atlantic concerns, not limited to the United States or Europe. Lord, having just completed eight years of service at the United Nations—as the US delegate, and as Eleanor Roosevelt’s successor as US representative to the Human Rights Commission—advocated a global mission for the Atlantic Council, one that combined political, economic, and military concerns into a pragmatic agenda carried out by transatlantic leadership. Henry Cabot Lodge, another member, was willing to accept Lord’s expansive mission for the Council, but only if it was limited to working with the free world and not with individuals or nations that did not subscribe fully to the Atlantic values of democracy and rights.

Will Clayton, largely known for his work as the economic administrator of the Marshall Plan, was hesitant to accept either Lord’s or Lodge’s inclusive international framework, and called for a more concentrated focus on building trade and investment between the United States and Europe.

Acheson shared Clayton’s reluctance to pursue a one-world approach, but for a different reason: He believed that the notion of global balance misinterpreted the true nature of the world. Acheson argued that the “North American–Western European connection was vital and made possible the development of Latin American, Asian, and African countries in security, and in an environment which leaves them freedom of choice to develop in their own way . . . The essential truth is that the hope of the whole free world, developed and undeveloped nations alike, lies in the ever closer association and economic growth of Western Europe and North America.”

Norstad expressed the conviction, which he stated was shared by President Kennedy, that “Atlantic unity represents the true course of history.” Norstad called this unity inevitable, but he also highlighted the complications, contradictions, and conflicts of ongoing national policies. In his view, no Atlanticist had yet determined precisely how these agreements could be achieved in practice, or how public support would be gained for various Atlantic priorities. Norstad stated that the Council’s core activities would include both determining the pragmatic agenda and garnering public support. In its first decade, the Council would grapple with how to make the best use of its new structure as a private policy organization—especially as it worked through the thorniest Atlantic issues, which no government or alliance could handle through official channels.

The world’s most effective peace machine

The Council co-founder Mary Lord expressed concern that the organization’s message was not resonating beyond the Beltway to Main Street America. In 1963, Lord urged her fellow board member Elmo Roper to apply his social-science skills to this problem, to gauge US public support for Atlantic cooperation, and then to convince Americans that NATO was indeed vital to American interests. This was the spark for the Council’s public campaigns which began in the organization’s second year, reaching their height with NATO’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1974.

Elmo Roper, a pioneer in market research who first made his mark during President Roosevelt’s outreach for the Lend-Lease deal, accepted Lord’s challenge. He proceeded to design and carry out one of the most comprehensive studies ever conducted of American attitudes toward foreign affairs in the postwar period. Roper’s poll examined American attitudes toward international alliances and, among other findings, showed that only 6 percent supported US withdrawal from its international commitments. At the same time, the poll also revealed that few Americans fully understood NATO operations.

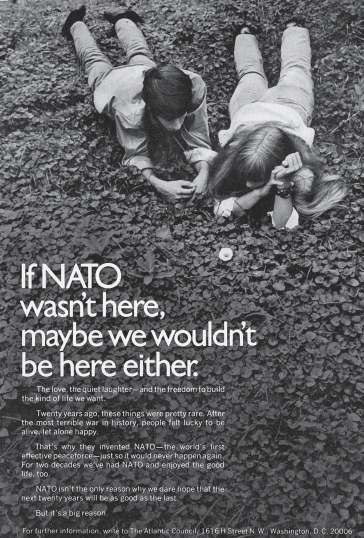

Roper and Theodore Achilles took the lead, recruiting J. Walter Thompson and his prominent Madison Avenue agency to provide free services to the Council in the late sixties and early seventies. The board signed off on the JWT slogan—”If NATO wasn’t here, maybe we wouldn’t be either”—and prepared a series of forceful print and broadcast messages, reaching out to 8,000 newspapers and 1,000 television and radio stations. According to broadcast and print ratings, the advertisements made more than 200 million home impressions during the course of the campaigns.

The Council’s public campaigns sought to modernize perceptions of NATO in the difficult environment of the mid- to late sixties, when Americans were exhausted and divided by the conflicts in Southeast Asia. After 1968, the Council repeatedly drew attention to the failures of the Prague Spring, when Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia.

The Council cited these failures as a reason to increase NATO’s capacity to maintain the West’s security, bringing attention to the need to address mutual force reductions.

The Council’s leadership was especially concerned about persuading the younger generation; they worried that youth mistook the war in Vietnam to be a NATO issue. JWT executives responded with words and images that they believed would “reflect the lifestyle of the youthful: contemporary, fresh, un-pious, that would tell it like it is.” JWT proposed slogans that would show NATO was not the world’s greatest war machine. They included language that underscored NATO’s non-military contributions—its so-called “third dimension effects,” defined as the economic, political, and social values of transatlantic security arrangements.

1960s.

The Council and JWT then recruited comedian Bob Hope, a passionate supporter of US service members, to be the campaign’s face and its first spokesman. Hope, who had hosted the Academy Awards on ten occasions and headlined numerous United Service Organizations (USO) shows, was an instantly recognizable national figure and an ardent believer in NATO as a critical defense against the threat of global communism. Hope lent his name to the Council’s print advertisements and recorded a number of radio spots for the Council, which were played nationwide in the late sixties and early seventies.

J. Walter Thompson Company. Domestic Advertisements Collection, Duke University

J. Walter Thompson Company. Domestic Advertisements Collection, Duke University

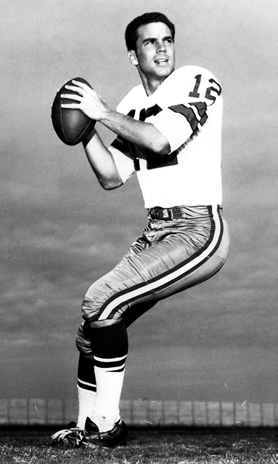

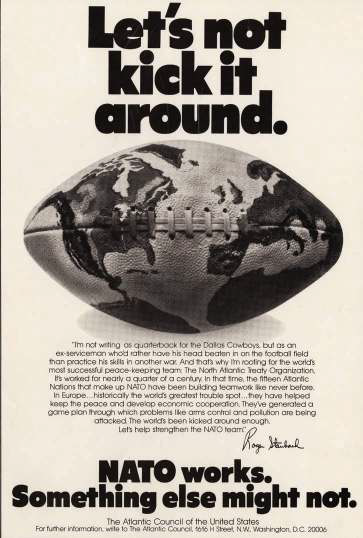

Following on the success of the Hope publicity, the Council recruited Roger Staubach—Dallas Cowboys quarterback and MVP of Super Bowl VI, as well as a Vietnam War veteran—for the next campaign in the early seventies, a targeted effort to reach young people in the run-up to NATO’s twenty-fifth anniversary year in 1974. The campaign would show them that NATO was an enterprise devoted to stability and harmony, and that it had been instrumental in warding off World War III for twenty years. In sum, the Council had determined its mission: to fortify the world’s greatest peace machine.

N. W. Collins is the chair of Defense and Security Studies at Columbia University.