Kenya, under President William Ruto, is reorienting its foreign policy approach to Africa and its diaspora, seeking to be a leader on the continent and across the Global South. Its proposed mission to Haiti emphasizes this keen interest.

In the aftermath of the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, the Caribbean republic has seen escalating gang violence that has threatened the political system and security. Between January and August of this year, 2,439 Haitians were killed, 951 were kidnapped, and 902 were injured. On October 3, the United Nations (UN) Security Council adopted resolution 2699, which approved a multinational mission, led by Kenya, to help the Haitian National Police defeat the onslaught of criminal gangs perpetrating violence and other crimes. Although the mission is UN-authorized, it is not an official UN peacekeeping mission. Kenya plans to lead the mission by sending over a thousand officers, a number that will be supplemented further by the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Antigua and Barbuda.

An intervention in a Caribbean state by an African country could perplex some given the vast physical distance between the regions and a lack of historic military and security support. However, the planned deployment aligns closely with Ruto’s foreign relations agenda.

Under Ruto’s presidency, Kenya has stepped up to play a more active role in regional and international politics and to secure for itself a leadership role in championing African interests. Kenya hosted the first Africa Climate Summit in September which concluded with the Nairobi Declaration, a document laying out a consensus among participating African countries about their climate priorities. Ruto also recently announced that Kenya will no longer require visas for visitors from all countries beginning January 2024 in an effort to boost tourism and international connectivity.

A policing mission to Haiti could further raise Kenya’s profile as a champion of African interests. While there has been little collaboration between African countries and Haiti historically, many Haitians are a part of the African diaspora. Since Haiti’s 1804 revolution and independence, the country has experienced repeated bouts of instability further worsened by nearly two decades of occupation by the United States (from 1915 to 1934), and subsequent UN-approved intervention missions, including one led by Brazil that ran from 2004 to 2017. For Kenya to achieve its newly oriented foreign-policy goals through this intervention, it would have to avoid repeating the failures seen in past missions and steer clear of channeling US paternalism.

In October 2022, Acting Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry authorized a request for foreign intervention through a written appeal to international partners. However, observers including the National Haitian American Elected Officials Network and the Family Action Network Movement are highly skeptical of further intervention and are concerned that supporting the unelected Henry government could worsen the nation’s political crisis. Those organizations have called on the Biden administration to withdraw US support for the mission.

Critics in Kenya have been asking another question: Who asked Kenya, specifically, to intervene? Officially, Kenya volunteered to lead the security force on July 29 in a statement by former Minister of Foreign Affairs Alfred Mutua. According to Mutua, the commitment came after a request by the “Friends of Haiti Group of Nations.” However, some observers argue that Kenya is leading the intervention to be a good “friend” to the United States. In September, the United States pledged one hundred million dollars in support to the intervention; days later, the United States and Kenya signed a defense agreement that included resources and support for security deployments.

Putting theories and unknowns aside, it is clear that Kenya is taking a newly proactive approach to the crisis in Haiti. That new approach underscores Ruto’s atypical foreign policy strategy, which aims to distinguish Kenya from its African peers globally and add to Nairobi’s list of accomplishments as a pan-African leader. Success in achieving that strategy could pave the way for greater influence in regional and international politics, setting Kenya up to challenge South Africa and Nigeria, who have historically been regional hegemons. But success in Ruto’s foreign policy approach depends, in part, on the success of this mission to Haiti—one that will be hard to come by.

To be sure, Ruto’s plan has faced numerous domestic challenges. On November 16, Kenya’s high court extended an order blocking the mission’s deployment pending a final decision in January 2024. Despite the court order, the mission was approved by the Kenyan Parliament.

There have also been signs that public support is mixed, as some people have questioned Nairobi’s priorities, arguing that it should focus on protecting lives in Kenya first. Currently, insurgencies are underway along the Somalia border and cattle banditry and clashes between nomadic pastoralists have challenged communities in Northern Kenya.

Amnesty International has also condemned the deployment, not just because of a “troubling history of abuses” associated with past interventions in Haiti, but also because of extrajudicial killings and excessive force used by the Kenyan police. These concerns about human rights violations raise questions as to whether the Kenyan police will be able to succeed in Haiti where other missions have failed.

Regardless, the first batch of police officers have begun training for their planned mission in Haiti. In preparation for the deployment, the director general of the Haitian National Police, alongside a delegation from the Haitian government, visited Kenya last week. However, in early November, Interior Minister Kithure Kindiki asserted that police officers will not be deployed to Haiti “unless all resources”—perhaps including extra funding from the United Nations, recently requested by Kenya—“are mobilized and availed.”

Former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta oriented Nairobi’s foreign policy more closely towards China. Ruto, on the other hand, appears more interested in seeking out partnerships with the West—particularly the United States. This year alone, at least six high-level US officials have visited Kenya: First Lady Jill Biden, United States Agency for International Development Administrator Samantha Power, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Trade Representative Katherine Tai, Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield, and Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry. Kenya and the Millennium Challenge Corporation also signed a sixty-million-dollar threshold program focused on urban mobility and growth in September.

At the same time, Ruto’s administration has also developed a new policy focused on pan-Africanism and, in its dealings beyond the continent, South-South cooperation. If Kenya were to achieve success in Haiti, which would require learning from the tough lessons of past interventions while incorporating the aspirations of Haitians, its global profile could benefit, and Nairobi could secure a status as a reliable ally to the United States both on the continent and beyond.

It remains to be seen whether Kenyan police will eventually be deployed to Haiti. If the deployment occurs, watch the mission closely: Success in helping Haiti secure its future, if attained properly and without repeating mistakes of the past, could see Kenya amplify its bid to claim a bigger seat on the world stage.

Sibi Nyaoga was a young global professional at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

Further reading

Wed, Aug 23, 2023

Piece by piece, the BRICS really are building a multipolar world

AfricaSource By

Coming out of the Johannesburg summit, the BRICS group has the potential to accelerate the process of dedollarization and the transition to a multipolar world.

Tue, Aug 1, 2023

There are high expectations for Nigeria’s new president. Here’s how he can fulfill them.

AfricaSource By

Bola Ahmed Tinubu does have an opportunity to set up Nigeria as an economic powerhouse and African superpower. Here's how he can seize it.

Fri, Jun 30, 2023

Boko Haram is a ghost. The US needs to recognize that.

AfricaSource By

Nigeria's new president will need to get all the help he can get—including from the United States—to address the jihadist insurgency that has engulfed the country’s north.

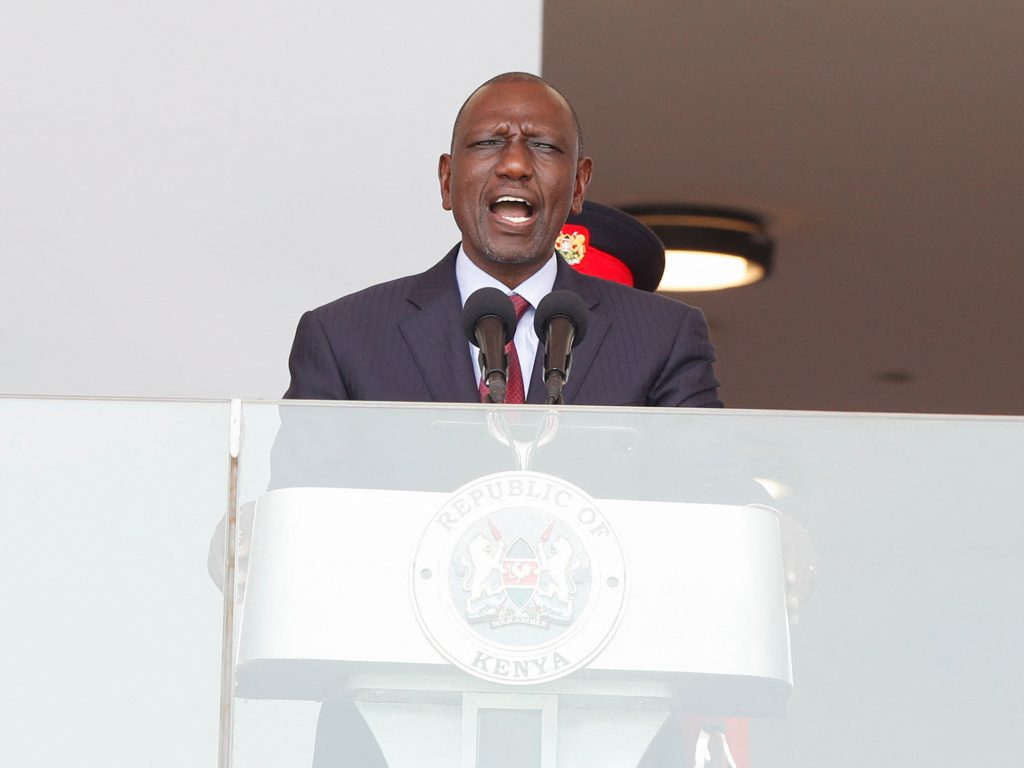

Image: Kenya's President William Ruto speaks during the country's 60th Jamhuri Day or Independence Day at the Uhuru Gardens in Nairobi, Kenya, on December 12, 2023. Photo via REUTERS/Monicah Mwangi/File Photo.