The solar eclipse across North America was not the only interesting story about the Moon this month. On April 2, the White House, through the Office of Science and Technology Policy, directed NASA and other federal agencies to work together to develop standard ways of keeping time on the Moon and beyond.

What did the White House ask for?

In a surprisingly technical (even for the Office of Science and Technology Policy), four-page memorandum, White House officials directed federal agencies to “develop celestial time standardization with an initial focus on the lunar surface and missions operating in Cislunar space.” In plain English, this means the ability to consistently tell time in outer space, beginning with the Moon and the space around it. It specifies that the time standard in space must be:

- referenced to the time standard on Earth (traceable),

- able to be relied upon for navigation and measurement (accurate),

- able to work if communication with Earth is disrupted (resilient), and

- extensible to space beyond the moon (scalable).

Why is it necessary to know the time on the Moon and elsewhere in space?

Although knowing the time may seem like a basic convenience, the ability to measure and keep time in a standard way with high accuracy is essential to a vast array of functions that depend on what is commonly referred to as position, navigation, and timing (PNT). The ability to know one’s location and navigate from place to place requires a reliable clock. This is why the now ubiquitous Global Positioning System (GPS) requires atomic clocks that are kept in sync by international standards. And those time standards and clocks are also essential for digital communications, including the high-speed transmission of data over the internet and through mobile networks. As the United States and other countries plan to send humans to the Moon over the next decade, the need for accurate and reliable PNT and communications makes it a priority to begin developing “Coordinated Lunar Time” now.

Why is it so hard to tell time in outer space?

Although the ticking of the seconds seems like an easy thing to rely on to tell time, the physics of time is much more complex. Thanks in large part to Albert Einstein, scientists understand that the relative passage of time on a clock changes depending on how fast it is moving (Einstein’s special relativity) and how much gravity it experiences (general relativity). Objects in space often move hundreds of times faster than any clock ever does on Earth (thousands of miles per hour) and the Moon’s gravitational pull is about one-sixth of Earth’s. As the Office of Science and Technology Policy memo explains, “to an observer on the Moon, an Earth-based clock will appear to lose on average 58.7 microseconds per day,” and that difference will fluctuate from day to day. While this discrepancy may seem miniscule, it will make it technically challenging to keep clocks in space in sync with those on Earth and with each other as needed for future PNT and communications.

What are the geopolitics of time standards for outer space?

This White House directive can be viewed within the larger context of the current rapid expansion of commercial activities in space and the parallel (if not competing) efforts of the United States and China to assemble coalitions to send humans to the Moon. The United States efforts fall under the Artemis Accords, and China’s under the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). While the Office of Science and Technology Policy memo notes that “international agreements will be necessary” to actually create a standard for time on the Moon, doing so will require global cooperation and leadership from both the International Bureau of Weights and Measures and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which create and synchronize time globally.

A focused effort by the United States now to develop a lunar time standard will dovetail nicely with the recent decision by the International Telecommunication Union to begin studying the related need to allocate electromagnetic spectrum frequencies for future development of communications on the lunar surface, and between lunar orbit and the lunar surface. It will also support the efforts of the Interplanetary Networking Special Interest Group (IPNSIG) of the Internet Society, an international nonprofit organization that has spent decades building the technical foundation for the expansion of the internet into space. In September 2023, the IPNSIG reported on the many outstanding challenges for the architecture and governance of a potential solar system-wide internet, including those associated with the need for standard time systems.

The United States and its Artemis partners will need to work through these existing multinational, consensus-driven bodies, especially in the near term, to coordinate with China and its ILRS partners on the development of solutions to the physics-based challenges of time standards in space. Space is already a dangerous and complicated place. For example, tens of thousands of objects in orbit, including debris and satellites, create rapidly growing challenges for maintaining space situational awareness globally. A future with competing time standards in space would only exacerbate those challenges.

Lloyd Whitman is senior advisor and fellow for science and technology policy at the Atlantic Council. He previously served at the National Institute of Standards and Technology as chief scientist and at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy as principal assistant director for physical sciences and engineering.

Further reading

Thu, Feb 15, 2024

Experts react: What to know about Russia’s apparent plans for a space-based nuclear weapon

Experts react By

Reports that Russia is developing a space-based nuclear anti-satellite weapon have raised national security concerns in Washington.

Fri, Oct 13, 2023

Mobilizing public science priorities through the American commercial space industry

GeoTech Cues By Ellie Creasey, Tiffany Vora

The next ten years stand to be transformative for improving life on our planet while simultaneously achieving a sustainable and thriving human presence beyond Earth.

Thu, Apr 27, 2023

Beyond launch: Harnessing allied space capabilities for exploration purposes

Issue Brief By Tiffany Vora

Tiffany Vora assesses current US space exploration goals and highlights areas where US allies are positioned for integration as part of Forward Defense's series on "Harnessing Allied Space Capabilities."

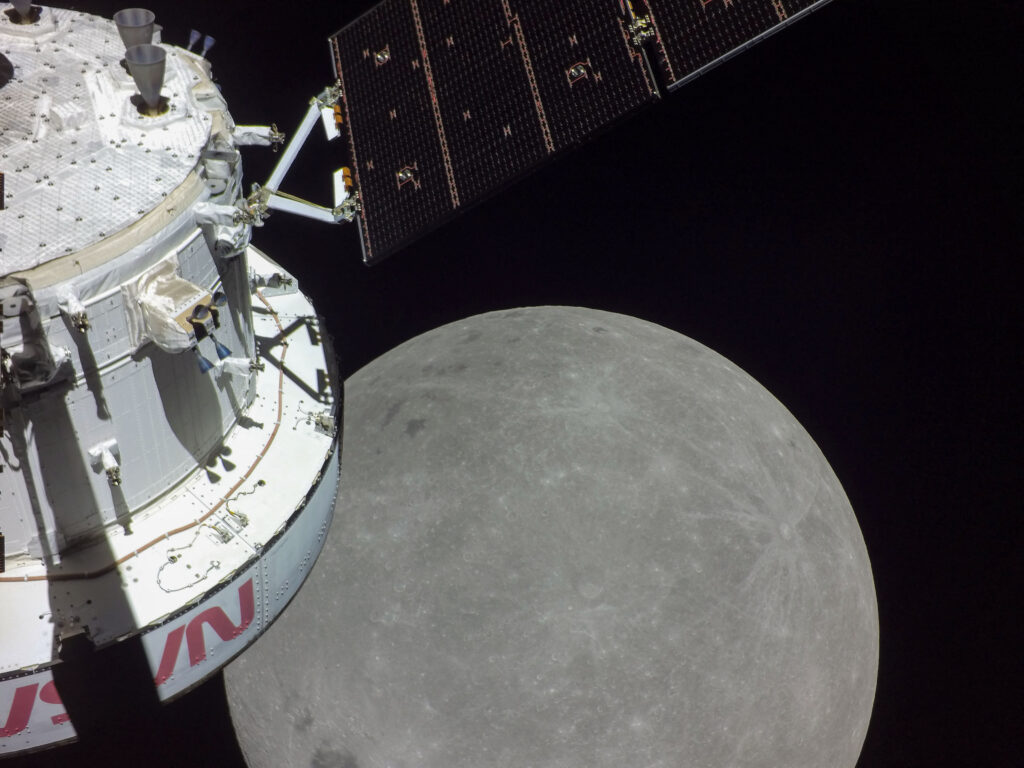

Image: Handout photo dated November 21, 2022 shows Artemis I, Flight Day 5. Orion spacecraft takes a selfie while approaching the Moon ahead of the outbound powered flyby - a burn of Orion's main engine that gets us into lunar orbit. During this maneuver Orion came within 81 miles of the lunar surface. Photo by NASA via ABACAPRESS.COM